The Adena and Hopewell Recreations of Marcia K. Moore: Living Images of the Ohio Valley Mound Builders based on Skeletal Remains and Artifacts

Jason Jarrell and Sarah Farmer

Adena

The earliest ancient people to construct widespread burial mounds and earthworks in the Ohio River Valley of the United States were participants in what is known as the Adena Culture. (“Adena” was named after the Ohio estate of Thomas Worthington near Chillicothe, Ohio where traits of this culture were first noticed). Adena first appeared around 500 BC and persisted until around 300 AD in Ohio, West Virginia, Indiana, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania. Adena people raised burial mounds ranging from just a few inches high to massive structures between 60 and 65 feet in height, such as the Grave Creek Mound in Marshall County, West Virginia and the Miamisburg Mound in Montgomery County, Ohio. The Adena also constructed circular and occasional squared earthwork enclosures. The circular enclosures are the most common, consisting of circular banks of earth with interior “ditches” following the inner wall and a single “causeway” entry way. These henge-like structures usually measure around 200 feet in diameter, and are generally believed to have been ritual or ceremonial centers used for a number of activities, such as rites of passage, feasting, funerary rites, and the processing of the dead.

In some instances, the Adena built large burial mounds insideof the circular enclosures. The Conus Mound at Marietta, Ohio represents a perfect example of this practice, consisting of a conical mound 30 feet high surrounded by a circular earth wall with interior ditch, 585 feet in circumference, with a causewayed entryway at the northwest. The mound-within-enclosure symbolism has been interpreted to represent a sacred Axis Mundi or holy mountain connecting the three realms of the Adena cosmos: the sky world, the earth disc, and the underworld (Romain 2015). The Adena Culture is known for its great diversity of mound construction and burial practices (Hays 2010), and possible social structures proposed by experts utilize models ranging from heterarchical to hierarchical in nature, likely reflecting intense regional diversity (Jarrell and Farmer 2017).

Adena shamans wore elaborate costumes incorporating parts of animals, including spatulas and face-masks made from the skulls and jaws of wolves and wildcats. It has been suggested that the Adena shamans may have been able to pierce the veil between worlds when assuming the transcendent merger with spirit animals such as wolves (Romain 2018). The Nicotiana rusticatobacco smoked in Adena tubular smoking pipes undoubtedly facilitated this process of transformation. Nicotiana rusticahas the highest concentration of nicotine of any known tobacco (in excess of 18%), and is demonstrably proven to cause hallucinogenic experiences identical in some cases to those induced by catalogued psychoactive substances.

In around 100 BC, some Adena communities in southern Ohio developed into the Ohio Hopewell Culture. As we have extensively documented (Jarrell & Farmer 2017), Adena burial sites throughout the Eastern Woodlands have frequently yielded the remains of male and female individuals reaching between 7 and 8 feet in stature with skeletal traits indicating powerful musculature.

In some instances, the Adena built large burial mounds insideof the circular enclosures. The Conus Mound at Marietta, Ohio represents a perfect example of this practice, consisting of a conical mound 30 feet high surrounded by a circular earth wall with interior ditch, 585 feet in circumference, with a causewayed entryway at the northwest. The mound-within-enclosure symbolism has been interpreted to represent a sacred Axis Mundi or holy mountain connecting the three realms of the Adena cosmos: the sky world, the earth disc, and the underworld (Romain 2015). The Adena Culture is known for its great diversity of mound construction and burial practices (Hays 2010), and possible social structures proposed by experts utilize models ranging from heterarchical to hierarchical in nature, likely reflecting intense regional diversity (Jarrell and Farmer 2017).

Adena shamans wore elaborate costumes incorporating parts of animals, including spatulas and face-masks made from the skulls and jaws of wolves and wildcats. It has been suggested that the Adena shamans may have been able to pierce the veil between worlds when assuming the transcendent merger with spirit animals such as wolves (Romain 2018). The Nicotiana rusticatobacco smoked in Adena tubular smoking pipes undoubtedly facilitated this process of transformation. Nicotiana rusticahas the highest concentration of nicotine of any known tobacco (in excess of 18%), and is demonstrably proven to cause hallucinogenic experiences identical in some cases to those induced by catalogued psychoactive substances.

In around 100 BC, some Adena communities in southern Ohio developed into the Ohio Hopewell Culture. As we have extensively documented (Jarrell & Farmer 2017), Adena burial sites throughout the Eastern Woodlands have frequently yielded the remains of male and female individuals reaching between 7 and 8 feet in stature with skeletal traits indicating powerful musculature.

Recreations

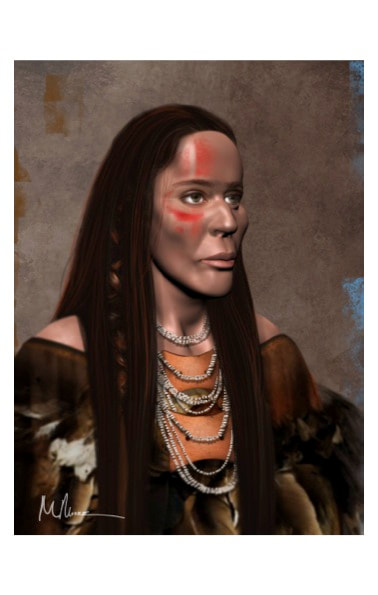

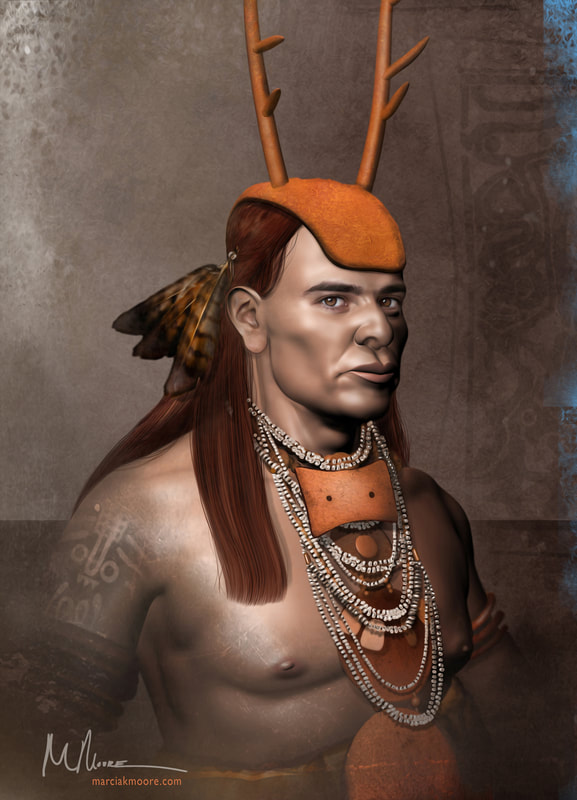

Between 2015 and 2017, we collaborated with the sensational artist Marcia K. Moore in a project to restore the living images of Adena and Hopewell people. Marcia’s talent for recreating the likenesses of ancient people by referencing actual ancient skulls and skeletal remains is well known, especially her work with the Paracas skulls of Peru. The “model” skulls used for the Adena male and female were chosen from an Adena burial site in Kentucky known as the Wright Mound. Physical Anthropologist H.T.E. Hertzberg (1940) regarded the Wright Mound crania as exemplary of the congenital traits of the Adena people, including large mandibles and high vaulted (brachycephalic) skulls. The Wright skulls also feature outstanding examples of the artificial cranial deformation (occipital flattening) by cradleboard practiced by the Adena. Frontal and profile photographs of the Wright skulls appear in The Adena People No.1by William S. Webb and Charles E. Snow (University of Kentucky, Lexington, 1945). The skull and facial skeleton used for the image of the living Adena male belong to burial 16 from the Wright Mound. Burial 16 was a 16-26 year old male buried in a log tomb measuring 5 x 7 feet, completely filled with clay. No artifacts were found with the body. The skeleton measured around 5.5 feet in length.

The Adena male is pictured wearing a copper anlter effigy headdress. Although this type of artifact is well known from Hopewell mounds in southern Ohio, a similar object was uncovered at the Adena-affiated Fisher Mound in Kentucky. These artifacts were connected with shamanic practices dealing with the Great Horned Serpent of the watery Underworld as known from the traditions of the Native American tribes of the Eastern Woodlands, Great Lakes, and the Plains.

For the Adena female recreation, the skull of Burial 13 from the Wright site was selected. William S. Webb and Charles Snow considered this specimen to be the best-preserved Adena female from Kentucky and a perfect example of the “Adena physical type”. Burial 13 was a young Adena female with a cranial index of 90.5, featuring sub-medium artificial deformation. Wright Burial 13 was found in a pit dug to 5.5 feet in depth into the east side of the mound. At the bottom of the pit the burial had been placed in a log box made up of two long logs on each side and one short log at each end. Logs also lined the walls of the sloping sides of the pit. Post molds in the tomb suggested that the structure had roof supports. Two large deposits of red ocher were found at the feet of the skeleton.

The head and face of Marcia’s Hopewell recreation were based on features of several Hopewell skulls also reproduced in Webb and Snow’s TheAdena People No. 1. This individual is depicted in the bear costume of the “Shaman of Newark”, represented by the famous Wray figurine found with a burial from the Cherry Valley Mounds at Newark, Ohio (see Jarrell & Farmer, this issue). When Charles Wray purchased the figurine in New York in 1962, the artifact was still accompanied by a paper containing the following details its discovery in 1881:

The Adena male is pictured wearing a copper anlter effigy headdress. Although this type of artifact is well known from Hopewell mounds in southern Ohio, a similar object was uncovered at the Adena-affiated Fisher Mound in Kentucky. These artifacts were connected with shamanic practices dealing with the Great Horned Serpent of the watery Underworld as known from the traditions of the Native American tribes of the Eastern Woodlands, Great Lakes, and the Plains.

For the Adena female recreation, the skull of Burial 13 from the Wright site was selected. William S. Webb and Charles Snow considered this specimen to be the best-preserved Adena female from Kentucky and a perfect example of the “Adena physical type”. Burial 13 was a young Adena female with a cranial index of 90.5, featuring sub-medium artificial deformation. Wright Burial 13 was found in a pit dug to 5.5 feet in depth into the east side of the mound. At the bottom of the pit the burial had been placed in a log box made up of two long logs on each side and one short log at each end. Logs also lined the walls of the sloping sides of the pit. Post molds in the tomb suggested that the structure had roof supports. Two large deposits of red ocher were found at the feet of the skeleton.

The head and face of Marcia’s Hopewell recreation were based on features of several Hopewell skulls also reproduced in Webb and Snow’s TheAdena People No. 1. This individual is depicted in the bear costume of the “Shaman of Newark”, represented by the famous Wray figurine found with a burial from the Cherry Valley Mounds at Newark, Ohio (see Jarrell & Farmer, this issue). When Charles Wray purchased the figurine in New York in 1962, the artifact was still accompanied by a paper containing the following details its discovery in 1881:

…about four feet below the surface, the workmen found the skeleton of a giant, and with it was found the stone bear…The bones of the skeleton were very large, the arm and thigh bones being much longer than those in man of this day and age of the world…They had evidently dug the grave or pit some four feet deep and buried this giant or whoever he may have been, and buried this image with him… (Dragoo & Wray 1964:196)

The Hopewell bear clan was the most influential group in their ancient society between 200 BC and 500 AD throughout the Illinois and Ohio River valleys. The reverence for the bear as a sacred animal associated with human origins and the struggle for survival continues in Native American traditions of the northeast to the present day.

References

Dragoo, Don W. and Charles F. Wray. 1964. Hopewell Figurine Rediscovered. In American Antiquity, Vol. 30, No.2, 195-199.

Hays, Christopher. 2010. Adena Mortuary Patterns in Central Ohio. In Southeastern Archaeology, Vol. 29, No.1, 106-120.

Hertzberg, H.T.E. 1940. Skeletal Material from the Wright Site, Montgomery County, Kentucky. In The Wright Mounds, Sites 6 and 7, Montgomery County, Kentucky, by William S. Webb, University of Kentucky Press, 83-102.

Jarrell, Jason and Sarah Farmer. 2017. Ages of the Giants: A Cultural History of the Tall Ones in Prehistoric America, Serpent Mound Books and Press, LuLu.com.

Romain, William F. 2015. An Archaeology of the Sacred: Adena-Hopewell Astronomy and Landscape Archaeology, The Ancient Earthworks Project.

Romain, William F. 2018. Werewolf Shamans in the Ancient Woodlands of the Eastern United States. Electronic document, academia.edu.

https://www.academia.edu/37433573/WEREWOLF_SHAMANS_IN_THE_ANCIENT_WOODLANDS_OF_THE_EASTERN_UNITED_STATES

Hays, Christopher. 2010. Adena Mortuary Patterns in Central Ohio. In Southeastern Archaeology, Vol. 29, No.1, 106-120.

Hertzberg, H.T.E. 1940. Skeletal Material from the Wright Site, Montgomery County, Kentucky. In The Wright Mounds, Sites 6 and 7, Montgomery County, Kentucky, by William S. Webb, University of Kentucky Press, 83-102.

Jarrell, Jason and Sarah Farmer. 2017. Ages of the Giants: A Cultural History of the Tall Ones in Prehistoric America, Serpent Mound Books and Press, LuLu.com.

Romain, William F. 2015. An Archaeology of the Sacred: Adena-Hopewell Astronomy and Landscape Archaeology, The Ancient Earthworks Project.

Romain, William F. 2018. Werewolf Shamans in the Ancient Woodlands of the Eastern United States. Electronic document, academia.edu.

https://www.academia.edu/37433573/WEREWOLF_SHAMANS_IN_THE_ANCIENT_WOODLANDS_OF_THE_EASTERN_UNITED_STATES