|

By Jason Jarrell

The Adena-Hopewell burial mounds and earthworks of the Ohio River Valley are perhaps the most famous prehistoric sites of the Eastern Woodlands of North America. Yet “Adena-Hopewell” was not confined to the Ohio Valley—in reality, this was a major cultural tradition that covered most of the territory east of the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean, and stretching from Ontario to Southern Florida. And while archaeologists have attempted for decades to explain this vast expansion with a “down the line” approach—the idea that ideologies and technological developments spread mainly by trade and not by the movements and activities of actual people—more recently the experts have had to acknowledge that indeed, there were specific peoples involved in the transmission of Adena-Hopewell culture, even if their ethnographic heritage may vary from one region to another (Pluckhahn et al. 2020). Since the mid-20th century it has been well established that Adena-Hopewell in the Ohio Valley developed from an older burial cult with two major ”forms” or variations, usually referred to as Red Ocher and Glacial Kame, which spans a period of roughly 1500—500 BC. From this time the earliest Adena mounds were raised—mostly in the Upper Ohio Valley and Southern Ohio. Around 200 BC, Adena entered a more elaborate “Late” phase, and then the Ohio version of “Hopewell” first appeared sometime around 50 BC, probably in the vicinity of Chillicothe. Late Adena and Ohio Hopewell overlapped and co-operatively interacted in the Ohio Valley from this point forward—hence the use of the term Adena-Hopewell—demonstrating their common heritage. What is less commonly understood is that the ancient progression of Red Ocher-Glacial Kame to Adena-Hopewell actually occurred over the entire Northeast and Midwest, from the Great Lakes to the Tennessee River Valley and throughout much of the North and Mid Atlantic regions. In other words, the cultural stream of which Adena-Hopewell is a part is not unique to the Ohio Valley, and it naturally follows that the answers to many of the questions regarding this ancient phenomenon will never be found by narrowly focusing upon what amounts to one of many regions blanketed by its influence. Bearing this in mind, we now turn to the millennia-spanning manifestation of this cultural stream in Southern Ontario. Meadowood-Glacial Kame In Southern Ontario the Red Ocher and Glacial Kame burial complexes are usually considered two components of the Meadowood Culture, which spans 1500 to 800 BC. Meadowood sites feature the same diagnostic burial styles and artifacts that are found in Red Ocher-Glacial Kame burials in Ohio. For example, at the Sartori Site on Leamington Ridge, Essex County, several red ocher covered burials—including at least one ocher-encased cremation—were found in a sand and gravel knoll. Artifacts recovered include 1 Sandal-Sole shell gorget, 1 bar type shell gorget, marine shell beads, 1 copper axe, 1 chert bi-face, 1 worked shell object, 1 polished bone awl, 1 cigar shaped tubular limestone pipe, and other objects (Donaldson and Wortner 1995). At the much larger Hind Site on the Thames River, the remains of 30-40 individuals were recovered from pits in a sandy knoll, many associated with red ocher, and several of the burials are suggestive of prestige or status, including a 13-year old adolescent buried with a modified black bear skull, cigar-shaped stone pipe, and a strand of 108 copper beads, among other artifacts (Donaldson and Wortner 1995). A cremated adult male was found in the same tomb as the adolescent, with red ocher, two birdstones, one three-holed circular marine shell gorget, one two holed rectangular slate gorget, and pyrite deposits. The burials and accompanying artifacts from Hind could just as easily be found in Late Archaic and even Early Adena burials in the Ohio Valley, and likely represent the same shamanic ideology. Hind has been dated back as far as 1370 BC (Ellis et al. 2009), and is considered one of a number of Late Archaic sites in Southern Ontario, Northwestern Ohio, and Southeastern Michigan which were interconnected in a regional sphere of cultural transmission and interaction (Stothers and Abel 2008). In other words, we are dealing with a major node in the greater cultural expansion across a wide region that eventually evolved into Adena-Hopewell. In fact, under the name of “Meadowood”, the Red Ocher-Glacial Kame complex of Ontario was connected with contemporaneous manifestations in Indiana, Pennsylvania, New York State, and along the Atlantic Coast. The New York State archaeologist William Ritchie (1965) identified the burial ritualism of Meadowood with the same cultural continuum that gave rise to the later local manifestations of Adena and Hopewell, and interpreted the selection of natural knolls and hills for burial sites to reflect the same principles behind the construction of artificial mounds for the dead. These conclusions parallel those of the Adena expert Don Dragoo (1963), who considered Adena-Hopewell to have developed in the Ohio Valley out of an expansion of the Red Ocher-Glacial Kame culture from the Great Lakes region. Middlesex-Adena In parallel to the cultural sequence of the Ohio Valley, the Red Ocher-Glacial Kame complex in Ontario evolved into the local form of Adena in the latter first millennium BC. In Southern Ontario, New York State, and some areas of the Atlantic Coast, Adena is known as the Middlesex Culture. Middlesex sites yield such diagnostic artifacts as bi-faces made of cherts from Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, stemmed Adena and Kramer points, leaf shaped blades, pop-eyed birdstones, and Adena amulets and gorgets. Middlesex chronology spans 400-100 BC (Ferris and Spence 1995). Beneath the See Mound on the Western end of Tidd’s island in Eastern Ontario, 12-15 Middlesex burials were found radiating outward from a large ash pile at the center of the mound floor, and several of the burials featured stone slabs over the heads and other parts of the bodies (Kenyon 1986). Similar burial arrangements were found at the Criel Mound at Charleston, West Virginia and the Kiefer and Wilmington Mounds in Ohio (Webb and Snow 1945:81). Diagnostic Adena burials have also been found in the Ottawa Valley. One of the tombs at the Morrison’s Island 2 site in Pembroke consisted of a pit 3 feet in depth, containing bundled human remains wrapped in birch bark with 200 copper beads, 2 Burlington chert bifaces, 1 Robbins point made of the same material, and another Robbins point made of Mercer flint, all heavily encrusted with red ocher and limonite. Robbins style spear points are a diagnostic feature of the Late Adena phase in the Ohio Valley, which commences at around 200 BC, which corresponds to recently obtained radiocarbon dates from the Morrison’s Island Adena burial at 2000 +/- 40 BP and 2210 +/- 40 BP (Pilon and Young 2009:198-199). The Lake Forest Middle Woodland Period: Regional Hopewell Cultures In Southern Ontario, the Middle Woodland Period—which in the Ohio Valley is synonymous with the emergence of Late Adena and Hopewell—begins around 300 BC. At this time technological evolution, burial ritualism, and the circulation of exotica parallel developments which archaeologists attribute to participation in the “Hopewell Interaction Sphere”. Diagnostic Hopewellian artifacts from sites in Southern Ontario include Snyders points, platform pipes, worked mica objects, copper and/or silver sheeted panpipes, copper ear spools, characteristic stone gorgets and pendants, and beads made of copper, silver, and marine shell (Ferris and Spence 1995:99). The development of Ontario Hopewell represents the same cultural chain that unfolded in Ohio and elsewhere: “early in the Middle Woodland period some Ontario groups were peripherally involved in a Middlesex-Adena network through which a variety of exotica circulated…That network was replaced by, or more probably evolved into, the Hopewellian interaction sphere” (Ferris and Spence 1995:101-102). Archaeologists have defined several different Hopewellian cultures in Ontario, including the Point Peninsula, Laurel, and Saugeen cultures. It is important to note however, that these cultures may be considered to represent variations of a single regional manifestation, sometimes referred to as the Lake Forest Middle Woodland. Point Peninsula-Hopewell The Point Peninsula-Hopewell Culture spans south-central Ontario, Southern Quebec, Western New York State, and the Atlantic seaboard. The Point Peninsula people constructed burial mounds and earthworks, many of which are concentrated in the Rice Lake and Trent River vicinities of Ontario, which obviously embody the same cultural heritage as their more famous counterparts in Southern Ohio. The Serpent Mounds site is located on the Northern shore of Rice Lake in Peterborough County, Ontario. There are nine burial mounds at this site, one of which—Mound E—is considered to be a serpent effigy. The serpent measures 194 feet in length, 25 feet in width at the base, and reaches a maximum height of 5-6 feet. Excavations of the Mound E serpent have revealed primary burials in sub-mound pits and on the surface of the mound floor, and secondary burials distributed in the body or fill of the mound—in total the serpent originally held the remains of over 60 individuals (Dillane 2010). Artifacts recovered from these burials include copper, shell, and silver beads, mandibles of timber wolf, bird, and bear, beak of loon, a limestone animal effigy, a massive double-bitted adze, one painted and one fragmentary turtle carapace, and other items. Besides being a serpent, the Rice Lake effigy resembles the well-known Serpent Mound of Ohio in several other interesting ways. For example, Mound F at Serpent Mounds is considered by some to represent an “egg” before the head of the Mound E Serpent, and has been found to contain at least 6 burials, one of which was an isolated “trophy skull” as found in many Adena and Hopewell mounds in the Ohio Valley. David Boyle (1897) excavated several of these burials in the late 1800s, and also reported the discovery of a layer of black earth mingled with ash and mussel shells, 4 feet from the surface at the center of the egg. Beneath this layer, Boyle found a circular formation of stones 3 feet in diameter at mound base, which showed evidence of being subjected to heat. In their own survey of the Ohio serpent, Squier and Davis (1848:97) mentioned a stone structure, which once stood within the oval or “egg” situated before the serpent’s open mouth that was very similar to the circular stone structure found by Boyle beneath the egg (Mound F) at the Rice Lake site: “The ground within the oval is slightly elevated: a small circular elevation of large stones much burned once existed in its centre; but they have been thrown down and scattered by some ignorant visitor, under the prevailing impression probably that gold was hidden beneath them.” Furthermore, although archaeologists have long denied that the Serpent Mound in Ohio ever contained burials, recent research by Jeffrey Wilson (2016) has turned up evidence that in fact, the effigy did once contain burials. Regarding the Ontario Serpent Mounds site, Spence and Harper (1968:55) state, “Mound burial might be a Hopewellian trait, though the serpent shape is possibly related to the Serpent Mound of Ohio, seemingly Adena.” Indeed, radiocarbon dates from the Ontario Serpent span 128-302 AD, overlapping the Late Adena and Hopewell cultures in the Ohio Valley (Johnston 1968:70-72). The Cameron’s Point site consisted of three Point Peninsula mounds and a shell midden located at the Eastern end of Rice Lake. One of the burials at the base of Mound C, consisted of the remains of a seven-year-old child with two necklaces of copper, silver and shell beads wrapped around the neck, one of which included a shell disk bead pendant. Lying upon the pedant were five shell beads and a silver panpipe cover (Spence and Harper 1968). The skull of another 6-7 year old child in Mound C rested upon a Hopewell-type platform pipe. The decidedly Hopewellian assemblages with these burials are mirrored by discoveries at the Levesconte Mound on the Northern bank of the Trent River in Northumberland County, which contained the disarticulated remains of at least 61 individuals buried with bundles of artifacts including shell beads and pendants, mica, copper awls, and copper and silver panpipe sheaths (Kenyon 1986). The remains of a 40-50 year old woman were associated with four panpipe covers—three of copper and one of silver—while the remaining panpipe covers were found with the remains of children. Radiocarbon dates obtained from bone samples at Levesconte Mound are 120 +/- 50 AD. and 230 +/- 50 AD (Doughtery 2003:16). Saugeen Culture—Adena-Hopewell Transition The idea that there was a Saugeen Culture in Southwestern Ontario was based on discoveries at the Donaldson site along the Saugeen River in Bruce County. This important site is multi-component, with features dating back as far as 770 BC—as such; we will focus here on the Middle Woodland Period components. Initially, archaeologists interpreted the differences between the Woodland period pottery at Donaldson and other Point Peninsula sites to indicate that a completely different culture was represented—hence the Saugeen Culture. However, a recent review of discoveries from the Donaldson site by Benjamin Mortimer (2012) indicates that the site is actually transitional between the regional Early and Middle Woodland cultures. In the language of Ohio Valley archaeology, this would mean that the site is a bridge in the evolution from Adena to Hopewell. There were two major periods of excavation at Donaldson, in 1960 and 1971, both of which revealed separate cemeteries. The burials unearthed in 1971 consisted of three burial pits containing the remains of 10-11 individuals buried as inhumations, partial cremations, and defleshed and dismembered skeletons (Finlayson 1977). Copper artifacts recovered include 2 panpipe covers, 1 awl, 1 bar, 1 bangle, 1 bead, 1 patch for a stone Hopewell-type earspool, and 1 fragment of scrap copper. As noted by Finlayson (1977:513), the Donaldson burials yielded “a number of artifacts diagnostic of Hopewellian cultures to the south.” The Hopewell aspect at Donaldson is especially apparent in the assemblage from a Middle Woodland period burial dated to between 100 B.C. and 200 A.D., in which human remains were found associated with a copper panpipe cover, worked mica sheets, a stone earspool, and other objects (Mortimer 2012:39). The Laurel Culture Around 200 B.C., a manifestation of Hopewell known as the Laurel Culture or the Rainy River Aspect emerged in Northwestern Ontario and Northern Minnesota in the U.S., and eventually spread into Eastern Manitoba, Southern Quebec, and areas of Northern Michigan. While people of the Laurel Culture engaged in interactions with other Hopewellian groups in Ohio, Illinois, and Southern Minnesota, Laurel itself is considered “a unique and independent entity” (Mather 2015:195) with strong ties to Point Peninsula and Saugeen Hopewell of Southern Ontario. Laurel is known for its incredible time range—spanning roughly 200 BC to sometime between 1100 and 1200 AD—making this the longest lasting manifestation of Hopewell Culture known. Radiocarbon ranges for Laurel in different regions include 150 B.C.—1190 A.D. in Northwestern Ontario, 30 A.D.—1030 A.D. in Manitoba, 30 A.D.—560 A.D. in Michigan, and 150 B.C.—650 A.D. in Minnesota (Arzigian 2012; Dawson 1981). This chronology indicates that Ontario and Minnesota manifestations of the Laurel culture—like Havana Hopewell in the Illinois River Valley—is older than Ohio Hopewell, which began in the first century BC. Like the Illinois Valley Havana, it is possible that Laurel was one of the initial regional points of emanation of “Hopewellian” influences through the trans-regional exchange networks that had existed since Late Archaic times. The Laurel material culture includes copper objects (such as beads, flakers, bracelets, and awls); antler harpoons, stemmed and notched projectile points, grinding stones, and potteries with similarities to Point Peninsula and Saugeen styles (Boyd et al. 2014). One of the most important sites of the Laurel Culture is the Grand Mound, which is one of a group of 5 mounds located on the Minnesota side of the Rainy River at the mouth of Big Fork River in Koochiching County. Grand Mound is 25 feet high, 100 feet in width, and 140 feet long, and features an extension or tail 200 feet in length. Long considered to be a type of effigy, recent research by David Mather (2015) suggests that Grand Mound represents the Muskrat character from a regional variation of the Earth Diver Myth: “In the world-creation (or re-creation) stories from many parts of the world, the Earth Diver plays a heroic role in the aftermath of a global flood. In these stories, some mud must be retrieved from deep under the water so that dry land can be magically created. Always a diminutive creature such as an insect or diving duck, the Earth Diver succeeds when stronger animals have failed and hope is fading. Oral traditions of a muskrat as the Earth Diver are known from Algonquian-speaking groups including the Ojibwe and Cree, as well as Siouan speakers including the Dakota” (Mather 2015:196). Indeed, Muskrat bones have been found in ritualized contexts in Hopewell mounds in Southern Minnesota and western Illinois, and it is widely accepted that some form of the Earth Diver Myth was central to the cosmology of Adena-Hopewell in nearly all of its manifestations. The area where the Grand Mound was constructed only emerged from beneath the water around 2500 years ago thanks to changing hydrology, and the site then remained a floodplain with occasional submergence. According to Mather (2015:200—203), the ancients may have created a Muskrat effigy at this specific place because the environment itself reflected the events of the Earth Diver Myth. Identity It is interesting that Mather mentions the traditions of the Ojibwa and Cree in connection with Grand Mound, since there is a growing mountain of evidence that it was the ancestors of the Algonquian speaking peoples of this region who were behind the cultures we have briefly discussed in this article. In a recent study of the mtDNA of the burial population of the Donaldson Site, Grant Karcich (2014) found that haplogroup X occurs at a 25% frequency, which aligns with the frequency of haplogroup X among the modern Algonquian speaking populations in the Great Lakes region. As explained by Karcich et al. (2006): “The Donaldson haplogroup results are consistent with modern Algonquian populations and are indicative of an Algonquian population in the northeast during the Middle Woodland period. In the northeast, where Donaldson occurs there are two modern native linguistic groups, the Algonquians and the Iroquoians. Algonquian populations contain haplogroups with high A and C, low B and D, and X up to 25 percent. Iroquoian populations have either high A or C and no haplogroup X.” DNA studies have demonstrated that Algonquian-speaking peoples are the primary carriers of haplogroup X in Eastern North America (Malhi et al. 2001). A review of the mtDNA of 185 full-blooded Native Americans by Malhi et al. (2001:42) found that “haplogroup X is both especially common and ubiquitous in Algonkian populations”. Native American haplogroup X is better known as “X2a”. X2a is a distinctly North American haplogroup, and is considered rare in comparison to the other four founder haplogroups (A, B, C, and D). To date, the earliest discovery of the X2a lineage in the United States is from the remains of Kennewick Man, discovered on the Columbia River in Benton County, Washington and dated to 8,690-8,400 BP (Bolnick and Raff 2015). Kennewick Man not only demonstrates the antiquity of X2a in North America, but also clearly points to a Western Pacific origin. There is strong linguistic and archaeological evidence that the original proto-Algonquians migrated from the Pacific Northwest many thousands of years ago, passing through the Columbia Plateau and eventually settling in to their ancient homeland in the Northeast. The history of haplogroup X corroborates this probability: “A central X haplotype is shared by Native Americans in the Northwest and Northeast, suggesting that this haplotype might be the founding X haplotype in eastern North America…haplogroup X is present in a more linguistically diverse population in the Northwest, whereas in the Northeast this haplogroup is mainly limited to Algonquian speakers. This is consistent with the hypothesis that haplogroup X was first introduced to the eastern part of North America by Algonquians emigrating from Northwestern North America…” (Malhi et al. 2002:916) Pointing out that “craniometric data is highly correlated with mitochondrial DNA data”, Karcich (2014:7-8) makes several critical observations relevant to the Northeastern Adena-Hopewell cultures: “Middle Woodland populations of Serpent Mounds and Donaldson cluster together and are also found in close association with historic Chippewa and Cheyenne, two Algonquian speaking groups. The historic Huron and North West New York populations form a separate cluster of their own. This analysis supports an in-situ development of Algonquians in the Great Lakes region dating back into the Middle Woodland period” (Karcich 2014:7). Another significant mtDNA study Dewar et al. (2010:2245) found that five individuals from the Great Western Park archaeological site on the Detroit River dating to 1043-1385 AD “showed genetic links with the Hind site, an Archaic site in southern Ontario.” One of the Great Western Park individuals exhibited an extremely rare haplogroup A transition at np 16234, which Dewar et al. (2010:2250) emphasize has only been documented for two known individuals, “a Cheyenne individual…and an individual from the Hind site, a Glacial Kame site dating back to approximately 2900 BP from Middlesex County, Southern Ontario”. Clearly there is some level of long term genetic continuity in the region, spanning the Late Archaic predecessors of Adena-Hopewell to modern Algonquian speakers. For decades, scholars have connected the cultures discussed in this article with specific ancestral Algonquian groups using linguistic and archaeological research that can now be seen to corroborate the evidence more recently obtained by the genetic and anthropological studies. J.V. Wright (1999) considered the Laurel Culture to be the heritage of the Ojibwa and Western Cree, and suggested that a marriage network existed between the people of the Laurel, Point Peninsula, and Saugeen peoples. J. Peter Denny (1994) suggested that the Eastern Cree are also descendants of the Laurel Culture—according to his theory, Eastern groups adopted the Cree language and engaged in marriage alliances with ancient Algonquians during the expansion of the Laurel Culture, facilitating participation in new ceremonial practices and exchange. The Algonquian Arapaho and Suhtai Cheyenne have also been associated with regional Laurel and Blackduck (600-800 AD) cultures (Clark 2012:34), and Barry Pritzker (2000) has traced the ancestral heritage of the Arapaho as far back as 3,000 years in the Red River Valley in Manitoba, Canada and Minnesota. The antiquity of the Algonquian ancestors in the Northeast is continually being pushed back in time by genetic research. In a large scale study cross referencing the DNA of ancient remains dating back to 4,800 years ago with that of modern Native American populations, Scheib et al. (2018:1) found that “the ancient Southwestern Ontario (ASO) population clusters with modern Algonquian speaking populations and the Ancient One [Kennewick Man]”. This dating overlaps the Laurentian Archaic-Old Copper Culture in the region, which is considered the original ancestor of the cult of the dead that evolved into Red Ocher-Glacial Kame and Adena-Hopewell (Dragoo 1963). Current studies of the mtDNA of individuals associated with the ancient Maritime Archaic Culture, which dates back as far as 7,500 BC, have even revealed certain X lineages that survived to continue on in Algonquian populations. Obviously, we are only beginning to understand the incredible time depth and vibrant cultural heritage of a people who—long before the discoveries discussed in this article—had already tried to tell us: “We have always been here.” We will visit some of the deeper ramifications of the Northeastern Anishinaabe legacy in the next installment of this series. Bibliography available upon request. Jason Jarrell is co-author of Ages of the Giants: A Cultural History of the Tall Ones in Prehistoric America (LuLu.com, 2017): https://www.lulu.com/en/us/shop/sarah-farmer-and-jason-jarrell/ages-of-the-giants/paperback/product-1rv687k6.html

0 Comments

By Jason Jarrell and Sarah Farmer

(This article is the second in a 2-part series and was written so as to naturally follow the first installment.) The Moon Goddess of the Eastern Woodlands For decades, archaeologists have consulted the traditions of historically known Native American tribes to interpret Adena-Hopewell iconography and practices. Romain (2018:329) has suggested that concepts related to ancient celestial observations as embodied at ancient earthworks sites may have also been passed down over the millennia in oral traditions, songs, dances, and designs on textiles and pottery. The tribes of the Eastern Woodlands have handed down ancient traditions of a certain cosmic personality connected with many—if not all—of the concepts that have been associated with the moon as expressed in the symbolism of the Adena-Hopewell culture. In the cosmology of the historic tribes, the sun was often representative of the Above Realm, while the Earth Realm was personified as an “Earth Mother” (Romain 2018:325). The Earth Mother is a “basic theme of eastern Woodland mythology and ideology” with extremely widespread distribution (Prentice 1986:249). As the literal embodiment of earth, she is generally considered the mother of all plant, animal and human life, and all that lives upon the earth originates in her womb and then returns to her upon death (Prentice 1986:249). Thus, the Earth Mother may be said to represent the cycle of life and death as observed in nature. In an important study, Guy Prentice (1986:250) established that in addition to representing the natural cycle of life, the Earth Mother is also “frequently connected with the underworld and a death goddess, and is also identified as a lunar deity.” In an earlier study, Ake Hultkrantz emphasized the dual aspects of the Earth Mother as an “earth and death goddess who reigns over the realm of the dead, and who is closely connected with the moon” (1957:218). As explained by Hultkrantz (1957:101), “In North America, as in the Old World, the earth and death goddess has lunar mythological associations.” In her role as supreme ruler of the Land of the Dead, the Earth Mother is usually known as “Old Woman” or “Grandmother”. Prentice (1986:254) discusses the themes consistently associated with this entity: “The mythical data…demonstrate how notably the death goddess, the lunar goddess, the ‘Old Woman,’ and the ‘Grandmother’ deities of the eastern Woodlands share each other’s traits and merge in their identifying characteristics…these various deities are, in effect, different aspects of the same concept, referred to here as the Earth-Mother.” The Earth Mother may then be understood to be a goddess of life, death, and the spirit world with multiple “aspects,” alternately represented by the earth and the moon. Algonquian Lore Although the Earth Mother-Death Goddess is prominent in the traditions of the historic Algonquian, Iroquoian, Siouan, and Creek tribes, the present study will focus on traditions handed down by Algonquian speaking peoples, for the same reasons as those cited by Lankford (2007c:15) for referencing Algonquian mythology in his study of Eastern Woodlands cosmology: “With so widespread a phenomenon, it is difficult to know where to focus to get clarity, but one key to the problem is to find a coherent and well-collected body of beliefs, ritual, and mythology. The Central Algonkian peoples appear to be excellent candidates for such a focus. They are a useful group for the examination of Eastern Woodlands cosmology, because their corpus is large and their presence in the territory north of the Ohio River appears to be of long duration.” In addition, there have been archaeological and anthropological studies indicating that the Adena-Hopewell people of ancient Ohio included ancestors of several historic Algonquian tribes, including the Sauk, Fox, Kickapoo, Mascouten, and Shawnee (Barnes & Lepper 2018; Callender 1979; Denny 1989; Griffin 1952; Prufer 1964; Stothers 1981; Stothers & Graves 1983, 1985; Tankersley & Newman 2016). Such studies complement research connecting local Adena-Hopewell manifestations in Southern Ontario and Minnesota to Algonquian ancestors whose descendants entered history as the Ojibwa and other Anishnaabeg peoples (Denny 1994; Fiedel 1991, 2013; Matthews 1987; Seeber 1982), further strengthening the probability that proto-Algonquian peoples participated in—and helped to shape—the widespread Adena-Hopewell phenomenon. Of course, it is equally probable that ancestors of Siouan, Creek, and Iroquoian peoples also engaged in and contributed to regional Adena-Hopewell cultural manifestations. Nokomis Among the Ojibwa the Earth Mother/Moon Goddess is known as Nokomis (or Me-suk-kum-me-go-kwa). At the dawn of creation, Nokomis fell to the earth and formed the earth island on the back of the Great Tortoise (Prentice 1986:253). Schoolcraft (1839:135) reported a tradition in which Nokomis was the daughter of the moon, who was married for a time before a rival tricked her into falling into the center of a lake that served as a portal to the Earth World below. However, Nokomis was already pregnant with her daughter—“the fruit of her lunar marriage”. This daughter was born on earth and was herself eventually impregnated by one of the Four Winds, and gave birth to several Manitouk before dying. One of the children was Nanabush, the great Algonquian culture hero, who was raised by his grandmother Nokomis in his mother’s stead (Vecsey 1983:89). Nokomis is thus known as “Grandmother Earth” who is “also identified with the moon” (Hultkrantz 1957:95). According to Jenness (1935:40), the Ojibwa of Georgian Bay considered the term “Grandmother” itself to be a title, which “signifies the moon”. As described in Part 1 of this article, the lunar focus of Adena-Hopewell earthworks alignments, charnel house orientations, engraved tablets, and artifact symbolism has been interpreted to suggest that the moon was considered a “celestial entity” closely associated with the passage of souls to the Land of the Dead along the Milky Way Path of Souls (Romain 2015b:66). In the traditions of the Ojibwa, Potawatomi, and Ottawa tribes, the lunar Nokomis is directly associated with this concept: “Some natives hold that the soul travels to its destination along the Milky Way. First it encounters an old, old man, Mishomis, the sun; next an old, old woman, Nokomis or Wabenokkwe, the moon, for whose gratification the faces of the dead were daubed with paint. Both Mishomis and Nokomis, but principally the latter, direct the soul on its further course” (Jenness 1935:109). According to the Parry Island Ojibwa, the journey of the soul takes it to “the wigwam of Nokomis, Grandmother Earth, grandmother of Nanibush and his brother Djibweabuth; and, passing beyond it…the village Epanngishimuk, the home of the dead” (Jenness 1935:109). Nokomis lives in the Land of the Dead with the slain brother of Nanabush, known as Wolf(or Djibweabuth) (Prentice 1986:253). Wolf is often depicted as a psycho pomp or guide of the dead, yet it is Nokomis who possesses the ultimate authority: In an Ojibwa tale a widow petitions that her husband be permitted to return to life, and Nokomis responds by ordering Wolf to restore the dead man’s soul (Jenness 1935:109). Jenness (1935:9) noted that the Parry Island clans “painted their faces to please the sun; but they decorated the faces of the dead with their clan paintings to please the sun’s sister, the moon.” Nokomis was not only a patron of the dead, but also of shamanic practitioners and healers among the living. According to an Ojibwa tradition, Nokomis herself took pity on the suffering of mankind and sent her Grandson Nanabush to distribute the first herbal cures (Vecsey 1983:145). In a similar tradition Nanabush in turn gave Nokomis authority over “all roots and plants, and other medicines, derived from the earth,” and commanded that she yield them to mankind only when requests were made in the proper ritual manner (Tanner 1956:355). Thus, Medicine Society members among the Parry Island Ojibwa considered Nokomis “the source of all power that exists in trees and shrubs and stones,” to which the practitioner must make offerings, or else “his remedies would lose their potency” (Jenness 1935:38). Midewiwin members made offerings to “Nokomis, the earth” by burying tobacco at the roots of healing plants (Jenness 1935:76). A similar tradition is recorded among the Potawatomi: “He [Nanaboojoo] has caused to grow those roots and herbs which are endowed with the virtue of curing our maladies, and of enabling us, in time of famine, to kill the wild animals. He has left the care of them to Mesakkummikokwi, the great-grand-mother of the human race…Hence, when an Indian makes the collection of roots and herbs which are to serve him as medicines, he deposits, at the same time, on the earth, a small offering to Mesakkummikokwi” (De Smet 1847:378-379). Alanson Skinner (1923:54) reported a group of shamans among the Sauk tribe known as the Sisa’ki’euk, who in order to divine the fates of ill patients isolated themselves within small cylindrical bark houses to contact various Manitouk, including Our Grandmother and her grandson Wisaka (the Sauk name for Nanabush). Significantly, Our Grandmother is associated with herbal and spiritual healing in both her earthen and lunar capacities. In an Ottawa tradition, the moon is the ruler of the East Quarter and is known as Wabenokkwe, or “Wabeno Woman,” “sister of the sun over whom she has charge” (Jenness 1935:30). The Wabeno were medicine men that consulted supernatural beings to obtain knowledge of healing remedies, as well as love and hunting medicines (Jenness 1935:62). According to information obtained from Ojibwa and Potawatomi informants, the first Wabeno practitioner—known as Bidabbans, or “Day-dawn”—obtained his powers directly from Nokomis-Wabenokkwe as the moon (Jenness 1935:62). Indeed, historic Algonquian shamans considered the moon to be a central source of spiritual power. Jenness documented three types of practitioners among the Ojibwa, Potawatomi, and Ottawa of Parry Island: the Wabeno (healer), the Djiskiu (conjuror), and the Kusabindugeyu(seer). While all of these practitioners obtained their abilities from personal spirit guides, they received their actual powerfrom the moon: “For the medicine-man exhausted himself physically and mentally whenever he practiced his art; too frequent exertion overstrained his powers, antagonized the supernatural being who had granted him his blessing, and brought about his death. Once a month, however, the moon, which renews the mysterious power in women, likewise renewed the medicine-man’s power, in that he could safely peer into the future or effect one cure every four weeks” (Jenness 1935:60). Kokomthena In an important ethnographic study, the Voegelins (1944:371) emphasized that the tribe known historically as the Shawnee is “unique among all the Eastern Woodlands Algonquian-speaking peoples in possessing a female supreme deity and creator.” This deity is none other than the Shawnee form of Our Grandmother, known as Kokomthena (Howard 1981:165-166). The male supreme being is only vaguely conceptualized in the Shawnee cosmogony, while Our Grandmother played the ultimate role—an Absentee Shawnee tradition reported by the Voegelins (1944:371) has it that while the idea of creation may have emanated from the mind of the Great Spirit, it was Kokomthena who carried out the act of creation. While some believe that Kokomthena was originally subservient to a male creator deity, there are Shawnee who claim that she has always been their chief supernatural (Lucas 2001). In fact, Kokomthena’s prominence among the Shawnee is evidenced by some of the earliest historic observers, including the chronicle of Henry Lewis Morgan (1993:52): “The Supreme Being anciently worshipped by them was a woman, and was worshipped as grand mother, Go-gome-tha-na, our grand mother…this grand mother they regard as the creator of man and of all plants and animals. It appears to have been the original worship of the oldest branch of the Shawnee Nation…” With such importance, it is no surprise that the Shawnee traditions of Our Grandmother have been considered “the most complete account of the Earth-Mother as expressed in the mythology of various Indian tribes” (Prentice 1986:254). As emphasized by Prentice (1986:252), Kokomthena is “a lunar goddess whose image is reflected in the moon.” In a creation narrative which the Shawnee Prophet shared with C.C. Trowbridge (1939:5), the Great Spirit once informed the Shawnee “That he was going to leave them and would not be seen by them again, and that they must think for themselves & pray to their grand mother, the moon, who was present in the shape of an old woman.” The face of the moon was considered to show the image of Kokomthena “bending over a pot, cooking”, and so the historic Shawnee held ceremonies to correspond with the full moon (Voegelin 1936:6). The Shawnee considered Kokomthena’s home to be in the Land of the Dead entered at the terminus of the Milky Way Path of Souls, with the moon serving as “her reflector or shade, through which her image is seen” (Howard 1981:167-169). Thus, like her Ojibwa counterpart Nokomis, Kokomthena is goddess of agriculture, fertility, and childbirth, and yet she is also a lunar “death goddess” whose true home is in the Otherworld (Prentice 1986:251-252). Comparing the Shawnee Kokomthena to her counterpart in the lore of the Fox Indians reveals a nearly identical tradition: “The moon is our grandmother…When she vanishes we say she dies, but we do not really mean that she is actually dead. Every time she appears during a year we give her a name. The dark shadow we see in her is a Fox Indian pounding hominy in a wooden bowl…The Earth is our grandmother. Even though the Moon is our grandmother, too, yet she and Earth are not sisters. We love our Grandmother Earth, because she loves us, and is kind and good toward us. She gives us all that we have. She feeds us, and lets us rest on her bosom. And when we die she watches over our bodies and lets our souls linger about the scenes of our former home for 4 days, and then lets them go on their journey to the home in the land beyond the setting sun” (Jones 1939:19-20). Like her Ojibwa counterpart, Kokomthena is said to have fallen from the Above World long ago and formed the Earth Island on the back of the Great Turtle amidst the primordial sea (Voegelin 1936). Although often imagined as an elder woman with white hair (Voegelin 1936:4), Kokomthena is also sometimes conceived as a powerful giant capable of lifting grown men and hiding them in cracks in her home (Howard 1981:165). Rather than a grandson (such as Nanabush), it is Kokomthena herself who assumes the central role in the Shawnee version of the Earth Diver myth: Following the all consuming flood, she calls the crawfish to bring her mud from below the depths to remake the earth, and is then aided by a buzzard, which dries the wet soil brought from beneath the sea by flapping its wings (Howard 1981:184). After using the mud to form the new Earth World, Kokomthena creates the first post-flood human couple, and lives among them, bestowing the gifts of tobacco, fire, and the first medicine bundles (Voegelin & Voegelin 1944:370). Thus like other forms of the Earth Mother, Kokomthena is the originator of healing through plants and medicines (Prentice 1986:251). Shamanism and Ceremonies Kokomthena concluded her primordial activities by teaching the ancestors of the Shawnee how to properly conduct all ceremonies and rituals, after which she returned to the Above World and specifically, to her home in the Land of the Dead (Callender 1978:628). She is therefore the source of all “manners, customs, and ceremonies,” known to various types of Shawnee ritual specialists (Prentice 1986:251). Diagnosticians, healers, ritual leaders, and those seeking the proper methods of preparing war and medicine bundles all engaged in visionary “spirit journeys” to reach Kokomthena’s lodge, where they obtained knowledge of plants and herbs, proper care for the sacred fire, and the structure of large ceremonies (Howard 1981:169; Irwin 2008:180-181). Those wishing to meet with Kokomthena took a long journey to the Western edge of the Earth Disk, following the same course of the souls traveling the Milky Way to the Land of the Dead (Howard 1981:166-167). At the Western Edge visitors would be received through a portal or window in the sky opened by Kokomthena, and when the visit was over, they would be lowered back down through the Above World, inhabited by birds and other winged creatures (Howard 1981:166-167). The close association of Nokomis-Kokomthena with medicine and rituals is significant in light of the evidence reviewed in Part 1 of this article suggesting that in addition to being a central component of ceremonies designed to facilitate the journey of the souls of the dead, the Adena-Hopewell moon was also connected with other forms of ancient shamanism. That Algonquian ritual specialists and healers traveled to the Above World to learn from Our Grandmother in her personal abode, serves as a historic parallel to the types of “shamanic” activities depicted on the engraved Adena tablets, several of which feature lunar azimuths and seem to depict shamans assuming the forms of bird men in “spirit flight” ascending and descending the Three Worlds of the Woodland cosmos on an Axis Mundi or sacred tree (Carr and Case 2006). The lunar influence was still an important factor in traveling the worlds in historic times, as evidenced by the vision quest of Ogauns(a great Anishnaabeg warrior), in which the descent into the first layer of the Beneath World could not be achieved “until the moon is full” (Jenness 1935:57). Our Grandmother is also associated with sacred trees, as Coleman (1962:91) reported a tradition that when Nokomis died, Nanabush wrapped her in birch bark and planted a cedar tree near her head: “Thus the birch and the cedar—both significant trees to the Ojibwa—entered into the burial and commemoration of Nokomis.” There are also traditions connecting Our Grandmother with sacred mountains serving as portals, reminiscent of interpretations of Adena-Hopewell burial mounds as holy mountains uniting the Earth Disk with the worlds Above and Below (Carr 2008; Romain 2015a). A Potawatomi tale tells of a man and several children who traveled “east to the place of sunrise” to obtain long life from Nokomis, a journey that took them across “the great water” and which lasted 10 years (Jenness 1935:31). Eventually they reached the lunar goddess, who was living inside of a mountain: “Now they came to a mountain. The lads could see nothing on it, but after their leader had walked around it four times a door opened into its interior, and an old woman, Nokomis, the moon, invited them to enter. She knew why they had come, for she could read their thoughts” (Jenness 1935:31). As explained in Part 1, copper and mica crescent ornaments found in Adena-Hopewell mounds have been considered lunar symbolic artifacts. The crescents have been found with individuals who appear to have been ritual specialists or guides of the dead, as well as sub-adults including teenagers and even several infants. In Shawnee tradition, children under the age of 4 were believed to possess the ability to speak with Kokomthena in her own secret language, but the sacred dialect was forgotten as soon as the child began speaking Shawnee proper (Voegelin 1936:4). There were also once shamans who lived among the Shawnee who apparently possessed the ability to speak this secret language, although they are said to have died out long ago (Voegelin 1936:4). According to Prentice (1986 p. 251), these beliefs are connected with the concept of cyclic reincarnation: “This association of children with Our Grandmother was tied to the belief that the souls of newborn children came from the land of the dead where the Creator lives. The souls of the dead were thus equated with the yet unborn.” According to an Eastern Shawnee tradition, some of the stars along the Milky Way are the habitation places of these souls not yet born (Howard 1981:168). At the appropriate time, Kokomthena sends them to earth, where they leap into the bodies of infants just prior to birth (Howard 1981:168). If this concept were translated back into ancient times, then it could mean that sites such as the Newark Earthworks in Ohio—where the greatest lunar emphasis is found—may not only have been connected with the journey of the souls of the dead, but also the incarnation of those about to be born. There were also some among the Shawnee who were born with an inherent lifelong relationship to Kokomthena. As explained by Lee Irwin (2008:182): “Some individuals are created with special insights and faultless speech and are able to translate the thoughts of Kokothena.” To “translate the thoughts” of the goddess of life and death whose image was seen in the awe-inspiring moon must have been a most potent and revered ability. Perhaps the Adena-Hopewell lunar crescents were signifiers of those believed to be born with this special relationship with Our Grandmother—individuals who could have gone on to serve as guides of the souls of the dead, shamans, healers, or as organizers and leaders of ceremonies. Furthermore, if the Adena-Hopewell earthworks and the rites of the dead were closely linked with the cycles of the moon and the solstices, then it would be a small leap to speculate that those who were born under the same influences may have been considered predestined for a special connection to associated other-than-human intelligences. The lunar Grandmother was also a highly sought after personal spirit guide. Historic Algonquian children were encouraged at an early age to fast for several days to initiate vision quests to obtain powers or abilities which they then possessed over the course of their entire lives (Irwin 2008:181). Among the Ojibwa, the sun and the moon were considered highly desirable pagawans (dream guardians or “spirit guides”) who could be contacted during such vision quests (Jenness 1935:54). Young Shawnee spirit travelers who established contact with Kokomthena became specialists in the most important practices, including healing with roots and herbs, the preparation of sacred medicines, and powerful magic affecting the hunt, agriculture, and warfare (Irwin 2008:181). As mentioned in Part 1, several crescent shaped mounds at the Newark Earthworks were surrounded by circular enclosures open to the area of the eastern sky where the waning crescent moon would be visible in the early hours—the same area where the Milky Way Path of Souls would appear to originate on the night of the summer solstice. This symbolism has been interpreted to indicate that the waning crescent moon was connected with the journey of souls to the Land of the Dead (Romain 2015a: 274), and could be related to the Adena-Hopewell ornamental crescents, which may have been worn by ritual specialists closely associated with the powerful lunar influence. It has been suggested that the Newark Earthworks were visited as a sacred location of pilgrimage in ancient times (Lepper 2016). Perhaps it was here that some visitors were ordained “oracles” or “servants” of the moon—which would explain why the appearance of lunar crescents in some Adena mounds located outside of Ohio has been interpreted as the addition of new types of cosmological powers to the local allied communities (Henry 2017; Henry and Barrier 2017). It has also been suggested that Adena groups may have curetted the remains of the dead for an unknown length of time before burial in a mound (Henry 2017), which may be connected with a tradition preserved by the historic Shawnee that the spirits of deceased relatives who joined Kokomthena in the Land of the Dead could sway her influence over the living (Prentice 1986:251). Earthworks as Myth Cycles in Hieroglyph There is an archaeological precedent for considering large, interconnected earthworks of the Eastern Woodlands as embodiments of entire mythic narratives. Between 1200 and 1600 AD, Algonquian people in North Central Michigan constructed ritual landscapes featuring burial mounds and circular earthwork enclosures with ditches and gateways (Howey 2012). As explained by archaeologist Meghan Howey (2012:161), “Late Prehistoric Anishinaabeg communities created rituals and constructed monuments with contrasting positions in the landscape to facilitate local community coherence (mounds) and regional exchange (earthworks) in a constantly evolving cultural landscape.” Thus the later earthworks in Northern Michigan are not only identical in form to many of the more ancient Adena-Hopewell sites in the Ohio Valley, but apparently also served a similar function in preserving social identity and facilitating exchange. Located in Aetna Township in Missaukee County and dated to cal. 1290-1420 AD, the Missaukee Earthworks consist of two circular ditched enclosures situated 2,130 feet apart on an east-west line. The western enclosure is 157 feet in diameter while the eastern enclosure is 174 feet in diameter, and both structures originally featured two gateways, one facing the opposite enclosure and the other oriented north-northwest (Howey 2012; Howey and O’Shea 2006). The site also includes several burial mounds. In their extensive research, Howey (2012) and Howey and O’Shea (2006) have found that the Missaukee Earthworks may have been built to embody in hieroglyphic fashion a founding legend of the Anishinaabeg Midewiwin Society. The legend is known as “Bear’s Journey,” as recorded by Ruth Landes between 1932 and 1933 and published in 1968. It tells of how “the Shell Covered One” sent Bear to deliver the “pack of life” and the secrets of the Midewiwin to the Indians. The landscape features of Bear’s journey between worlds are also portrayed in pictogram form on Midewiwin birch bark scrolls as well as on a diagram drawn by Will Rogers (“Hole in the Sky” of the Red Lake reservation near Bemjim, Minnesota) for Ruth Landes (1968:107). Howey and O’Shea (2006:274) found that the illustrated Bear’s Journey diagram-narrative conforms exactly to the layout of the Missaukee Earthworks: “What is particularly striking about Rogers’s drawing is the way in which the journey is represented in the drawing; it encompasses two large circles with a circular path between them, and a series of prescribed stops or locations along this cyclical path at which particular events are enacted or recounted…When the plan of the Missaukee precinct is compared to Rogers’s diagram…the similarities are remarkable. The respective size of the circles, the route of travel between the two circles, the location of water, the topographic setting and even the directional orientation all match. Along the projected pathway between the enclosures there are specific activity areas or stations and these appear to be repeatedly used…” This interpretation of the Late Prehistoric earthworks in Northern Michigan not only lends credence to the theory of Dr. Romain (2015a, 2015b), which connects Adena-Hopewell earthworks spanning many miles of Ohio together in a grand representation of the Path of Souls cosmology, but also suggests that legends concerning specific Manitouk might be enshrined at certain sites. Returning to certain features of the Newark Earthworks elaborated in Part 1, it will be recalled that the Great Circle is a circular enclosure likely representing the Earth Disk and therefore possibly referencing the Earth Diver myth. Within the circle are the large “Eagle Mound” and temple, as well as a lunar crescent earthwork. The bird shaped temple has been found to contain (among other things) a heavily burned clay basin and a copper crescent on the floor, and has been interpreted as a place where the bodies of the dead were prepared before later burial in the nearby Cherry Valley mounds. All of this was done under the auspices of the lunar influence, as evidenced by the lunar alignments of the Great Circle, the interior “Eagle Mound” temple, and Crescent earthwork. The role of Kokomthena in the Earth Diver myth has already been explored above. Yet here it should be also be explained that in Shawnee lore, several important types of Manitouk serve as Tipwiwe—or “truth bearers”—of Kokomthena. These are her servants in maintaining cosmic order, and include the four winds and four serpents of the cardinal directions, the great Thunderbirds, and celestial bodies such as the sun, stars, and meteors (Irwin 2008:180). Other important truth bearers of Kokomthena include eagles, tobacco, fire, water, and earth (Callender 1978:628) The sacred tobacco and fire serve as smoke offerings that carry prayers directly to Kokomthena, while the Shawnee consider the Thunderbirds to be the chief gatekeepers or custodians to the Above Realm (Irwin 2008:180). Thus, the combined elements of the Newark Great Circle may all find reference in the lore of Kokomthena as a lunar entity functioning as caretaker of the souls of the dead, the re-creator of the Earth following the deluge, receiver of prayers in the form of fire and smoke offerings, and as master of the Thunderbirds as guardians to the entrance of her abode in the Above World. There is a precedent for these types of interpretations of Adena-Hopewell earthworks. For example, the Great Serpent Mound in Adams County Ohio is widely believed to have served as the terrestrial representation of the entity known in Native American lore as the Great Horned Serpent. This malignant Manitou was the tester of the souls of the dead and the chief opponent of Our Grandmother’s grandson Nanabush in Algonquian tradition. Yet there is no reason to expect that only those mythic personalities from Native American traditions that are well known and easily recognizable—such as the Thunderbirds and the Great Horned Serpent—would be the only ones represented in the ancient earthworks and iconographic artifacts of Adena-Hopewell. Like the Late Prehistoric mounds and earthworks of Michigan, those of Adena-Hopewell may have served as hieroglyphic representations of myth cycles inscribed on the earth itself. If the Algonquian myth cycles of the Lunar-Earth Grandmother are transposed over the interrelated network of Adena-Hopewell earthworks sites scattered across a broad swath of Ohio (see Part 1), then certain “centers” of ritual and mound building activity may take on new meaning. For example, if the Newark area is considered a point of entry of the influence of the moon in the journey of the dead, then it may also have been the location where Our Grandmother was thought to have descended from the moon and laid the foundations of the Earth World or Island as formed from the soil brought from beneath the primordial sea. In fact, the area of the Newark Earthworks has even been interpreted to represent the “Island Earth” formed in the Earth Diver myth (Romain 2005). Flint Ridge Applying the concept of “mythic geography” to the larger Newark area allows for the possible identification of yet another possible component of Adena-Hopewell cosmology that may be expressed in Algonquian lore. Located about 9 miles east-southwest of the Newark Earthworks, Flint Ridge is a vein of high quality flint stretching for nearly 8 miles in Licking and Muskingum counties. Flint Ridge flint was the most important symbolic lithic material in the Ohio Hopewell culture and was used to create bifaces, cache blades, and other objects found in high concentrations at sites in the Ohio Valley, as well as culturally affiliated sites throughout the greater midcontinent (Lepper et al. 2001). Lepper et al. (2001:70-71) suggest that Flint Ridge flint was a symbolic indicator of cultural identity, and that specialized trips were made to procure the material in order to create artifacts to be given as gifts and presented during ceremonies at the major earthworks centers. If the Flint Ridge blades were distributed to pilgrims or people of influence traveling to the earthworks centers from other regions as a way of symbolically unifying dispersed groups in the ideology of the Hopewell Interaction Sphere, it is likely that such a material would be imbued with a spiritual meaning: “Possession of the exotic items may have reminded the recipients of the social connections signified by the gifts and the spiritual power embodied by the exotic object itself” (Lepper et al. 2001:71). Romain (2015a) points out that if plotted from the center of the Newark Octagon at around 100 AD, Flint Ridge would be situated on the azimuth of the moon’s south minimum rise, and a line drawn along this azimuth would even intersect the area where the epicenter of the prehistoric quarries were located. Located on the western terminus of Flint Ridge overlooking Claylick Creek, the Hazlett Mound Group consisted of three mounds surrounded by an enclosure wall made up partly of flint blocks (Carskadden and Fuller 1967). When William Mills (1921) excavated the largest mound of the Hazlett Group, he uncovered a square tomb made of flint blocks, measuring 37 x 37 feet around the outside with walls averaging 6 feet in height and 10 feet in width at the base and featuring a doorway at the southeast. Postholes in the corners suggested that the tomb had once been roofed, and a fireplace at the center showed evidence of repeated burning; containing charred wood mixed with ashes and earth (Mills 1921:230-234). Two burials were found in the tomb, but the features—including the constructional use of flint blocks, the fireplace, and the surrounding enclosure made of flint—clearly suggest that the structure may have been used in rituals before the burials were made. Just west of the main Hazlett Group was a smaller circular enclosure of earth, which surrounded an inner earthwork shaped like a crescent moon. Romain (2015a: 47) interprets the combination circle and crescent enclosure to be a symbol of the moon, and suggests that the presence of this earthwork at the terminus of a lunar sightline connecting the Newark Octagon and Flint Ridge indicates a “symbolic association” between the sites. Thus, a possible connection exists between the Newark lunar symbolism and the spiritual meaning of the Flint Ridge area in the Adena-Hopewell culture. In fact, the belief that flint is a living Manitou or spiritual intelligence was once widespread among Algonquian speaking tribes (Vecsey 1983:92). William Jones (1939:23) recorded a tradition of the Fox Tribe of Algonquian Indians that all flint originated from a single spirit being: “It is believed that there is a thick layer of flint far down beneath the surface of the earth. The Indians claim that all the flint they use comes from this source and that only they know where to look for it. This flint is looked upon as a manitou.” In a Menominee tradition originally reported by Hoffman (1896:87), the Flint Being first grew from out of the Earth Mother herself and attained sentience. Eventually, the Flint Being created a bowl and dipped it into the Earth. The earth in the bowl then turned into blood, which transformed again into a rabbit, which proved to be the alternate form of the great Algonquian culture hero Nanabush, grandson of the Lunar-Earth Grandmother. Perhaps some form or precursor of these traditions was once incorporated into the sacred meaning of the Newark area landscape by Adena-Hopewell. Since the Newark Earthworks clearly “bring the moon down to earth” with their extensive and sophisticated alignments, the nearby Flint Ridge could easily have taken on the symbolic reality of the sacred Flint Being emerging from the belly of the Earth aspect of Our Grandmother. By building the large Hazlett mound with its flint temple and enclosure and the nearby crescent shaped mound at the western terminus of Flint Ridge, the Adena-Hopewell may have intended to extend the lunar focus or aspect of the Great Mother to the source of their most sacred stone. The Face of the Adena-Hopewell Moon The archetypal female Manitou discussed in this article is a widespread figure in the traditions of many Native American peoples of the Eastern Woodlands. She is the embodiment of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth, as well as the source of medicine and great spiritual power—all reflected in her dual aspect as a goddess of both the earth and the moon. Like other other-than-human personalities—such as the Thunderbirds and the Great Underworld Serpents—reference to the Moon-Earth Mother can be found in the ancient iconography and celestial alignments of ancient earthworks and artifacts of the Ohio River Valley. While the mythology surrounding this figure undoubtedly evolved and changed over the millennia, the traditions of the historic Ojibwa, Shawnee, Fox, and other Algonquian speaking tribes, may still offer a glimpse of the true face of the Adena-Hopewell moon. Jason and Sarah are the authors of Ages of the Giants: A Cultural History of the Tall Ones in Prehistoric America, available on LuLu.com. Visit their website: paradigmcollision.com References Barnes, Benjamin J. & Bradley T. Lepper. 2018.Drums Along the Scioto: Interpreting Hopewell Material Culture Through the Lens of Contemporary American Indian Ceremonial Practices. Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress. Callender, Charles. 1978. Shawnee. Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 15: Northeast, ed. Bruce G. Trigger, Smithsonian Institution, pp. 622-635. 1979. “Hopewell Archaeology and American Ethnology.” Hopewell Archaeology: The Chillicothe Conference, ed. D. S. Brose and N. Greber, pp. 254-257. Carr, Christopher. 2008. World View and the Dynamics of Change: The Beginning and the end of Scioto Hopewell Culture and Lifeways. The Scioto Hopewell and Their Neighbors: Bioarchaeological Documentation and Cultural Understanding, ed. D. Troy Case and Christopher Carr, Springer Science and Business Media, pp. 289-333. Carr, Christopher and D. Troy Case. 2006. The Nature of Leadership in Ohio Hopewellian Societies: Role Segregation and the Transformation from Shamanism. Gathering Hopewell: Society, Ritual, and Ritual Interaction, ed. Christopher Carr and D. Troy Case, Springer, pp. 177-237. Carskadden, Jeff and Donna Fuller. 1967. The Hazlett Mound Group. Ohio Archaeologist Vol. 17 No. 4, pp. 139-143. Clay, Berle R. 2013.Like a Dead Dog: Strategic Ritual Choice in the Mortuary Enterprise. Early and Middle Woodland Landscapes of the Southeast, ed. A.P. Wright and E.R. Henry, University Press of Florida, Gainsville, pp. 56-70. Clay, Berle R. and Charles M. Niquette. 1992. Middle Woodland Mortuary Ritual in the Gallipolis Locks and Dam Vicinity, Mason County, West Virginia”, West Virginia Archeologist, 44 (1-2), pp. 1-25. Coleman, Bernard. 1962.Ojibwa Myths and Legends. Ross & Haines, Minneapolis. De Smet, G. 1847.Oregon Missions and Travels over the Rocky Mountains in 1845-1846. Edward Dunigan, New York. Denny, Peter J. 1989. Algonquian Connections to Salishan and Northeastern Archaeology. Papers of the 20th Algonquian Conference, ed. William Cowan, Carleton University, Ottawa, pp. 86-107. 1994. Archaeological Correlates of Algonquian Languages in Quebec-Labrador. Actes 25e Congres des Algonquinistes, ed. William Cowan, Carleston University Press, Ottawa, pp. 85-105. Fiedel, Stuart J. 1991. Correlating Archaeology and Linguistics: The Algonquian Case. Man in the Northeast 41, pp. 9-32. 2013. Are Ancestors of Contact Period Ethnic Groups Recognizable in the Archaeological Record of the Early Late Woodland? Archaeology of Eastern North America Vol. 41, pp. 221-229. Griffin, James B. 1952. “Culture Periods in Eastern United States Archeology.” Archaeology of Eastern United States, University of Chicago Press, pp. 352-364. Hall, Robert. 1979. In Search of the Ideology of the Adena-Hopewell Climax. Hopewell Archaeology: The Chillicothe Conference, ed. David S. Brose and N’omi Greber, Kent State University Press, pp. 258-265. 1997. An Archaeology of the Soul: North American Indian Belief and Ritual. University of Illinois Press. Hallowell, Alfred Irving. 1934. Some Empirical Aspects of Northern Saulteaux Religion. American Anthropologist (New Series) Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 389-404. 2002. Ojibwa Ontology, Behavior and World View. Readings in Indigenous Religions, ed. Graham Harvey, Continuum, London & New York. Hemmings, Thomas E. 1984. Investigations at Grave Creek Mound 1975-76: A Sequence for Mound and Moat Construction. West Virginia Archeologist, 36 (2), pp. 3-45. Henry, Edward R. 2017.Building Bundles, Building Memories: Processes of Remembering in Adena-Hopewell Societies of Eastern North America. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory Vol. 24, Issue 1, pp. 188-228. Henry, Edward R. and Casey R. Barrier. 2016.The Organization of Dissonance in Adena-Hopewell Societies of Eastern North America. World Archaeology, 48 (1), pp. 87-109. Hively, Ray and Robert Horn. 2016.The Newark Earthworks: A Grand Unification of Earth, Sky, and Mind. The Newark Earthworks: Enduring Monuments, Contested Meanings, ed. Lindsay Jones & Richard D. Shiels, University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, pp. 62-94. Hoffman, Walter James. 1896. The Menomini Indians. 14th Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution (1892-1893). Government Printing Office, Washington, pp. 11-328. Howard, James H. 1981. Shawnee! The Ceremonialism of a Native American Tribe and Its Cultural Background. Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio. Howey, Meghan C.L. 2012. Mound Builders and Monument Makers of the Northern Great Lakes, 1200-1600. University of Oklahoma Press. Howey, Meghan C.L. and John M. O’Shea 2006. Bear’s Journey and the Study of Ritual in Archaeology. American Antiquity 71 (2), pp. 261-282. Hultkrantz, Ake. 1957.The North American Indian Orpheus Tradition. The Ethnological Museum of Sweden, Monograph Series, Publication 2, Stockholm. Irwin, Lee. 2008. Coming Down From Above: Prophecy, Resistance, and Renewal in Native American Religions. University of Oklahoma Press. Jenness, Diamond. 1935. The Ojibwa Indians of Parry Island, Their Social and Religious Life. National Museum of Canada, Bulletin No. 78, Ottawa. Jones, William. 1901. Episodes in the Culture-Hero Myth of the Sauks and Foxes. The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 14, pp. 225-239. 1907. Fox Texts. Publications of the American Ethnological Society Vol. 1, ed. Franz Boaz. Late E.J. Brill Publishing, Leyden. 1939. Ethnography of the Fox Indians. Government Printing Office, Washington. Landes, Ruth. 1968. Ojibwa Religion and the Midewiwin. University of Wisconsin press, Madison. Lankford, George E. 2007a. Reachable Stars: Patterns in the Ethnoastronomy of Eastern North America. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa. 2007b.“The Great Serpent in Eastern North America.”Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms: Interpretations of Mississippian Iconography, ed. F. Kent Reilly and James F. Garber, University of Texas Press, Austin, pp. 107-135. 2007c.“Some Cosmological Motifs in the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex.” Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms: Interpretations of Mississippian Iconography, ed. F. Kent Reilly and James F. Garber, University of Texas Press, Austin, pp. 8-38. Lepper, Bradley T. 2016. The Newark Earthworks: A Monumental Engine of World Renewal. The Newark Earthworks: Enduring Monuments, Contested Meanings, ed. Lindsay Jones & Richard D. Shiels, University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, pp. 41-61. Lepper, Bradley T., Richard W. Yerkes, and William H. Pickard. 2001. Prehistoric Flint Procurement Strategies at Flint Ridge, Licking County, Ohio. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology Vol. 26 No. 1, pp. 53-78. Lucas, David M. 2001.Our Grandmother of the Shawnee: Messages of a Female Deity. Paper presented at the National Communication Association, Atlanta, Georgia. Matthews, Geoffrey J. 1987.Historical Atlas of Canada, University of Toronto Press. McConaughy, Mark A. 2015.The Nature and Cultural Meaning of Early Woodland Mounds in Southerwestern Pennsylvania and the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia. Pennsylvania Archaeologist Volume 85 (1), pp. 2-38. McCord, Beth K. and Donald R. Cochran. 2008.The Adena Complex: Identity and Context in East-Central Indiana. Transitions: Archaic and Early Woodland Research in the Ohio Country, ed. Martha P. Otto & Brian G. Redmond, Ohio University Press, pp. 334-359. Mills, William C. 1907.Excavations of the Adena Mound. Certain Mound and Village Sites in Ohio, Press of F. J. Heer, Columbus, Ohio, pp. 5-28. 1921. Flint Ridge. Certain Mounds and Village Sites in Ohio, Vol. 3, Part 3. F.J. Heer Printing Co., Columbus. Moorehead, Warren K. 1892. Primitive Man in Ohio. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, London, New York. Morgan, Henry Lewis. 1993.The Indian Journals 1859-1862. Dover Publications, N.Y. Olson, Eric C. 2016. A Systematic Analysis of Behavior at Late Early Woodland Paired-Post Circles, Master of Arts Thesis, Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana. Prufer, Olaf. 1964. “The Hopewell Complex of Ohio.” Hopewellian Studies, ed. Joseph R. Caldwell and Robert L. Hall, Springfield, pp. 35-83. Prentice, Guy. 1986. An Analysis of the Symbolism Expressed by the Birger Figurine. American Antiquity Vol. 51, No. 2. Purtill, Matthew P., Jeremy A. Norr, and Jonathan B. Frodge. 2014.Open-Air ‘Adena’ Paired-Post Ritual Features in the Middle Ohio Valley: A New Interpretation. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 39 (1), pp. 59-82. Romain, William F. 1991. Calendric Information Evident in the Adena Tablets. Ohio Archaeologist 41 (4), pp. 41-48. 1992a. Azimuths to the Otherworld: Astronomical Alignments of Hopewell Charnel Houses. Ohio Archaeologist 42 (4), pp. 42-48. 1992b. Further Evidence for a Calendar System Expressed in the Adena Tablets. Ohio Archaeologist 42 (3), pp. 31-36. 2005. Newark Earthwork Cosmology: This Island Earth. Hopewell Archaeology Newsletter, Vol. 6 No. 2. 2009. Shamans of the Lost World: A Cognitive Approach to the Prehistoric Religion of the Ohio Hopewell. Rowman & Littlefield. 2015a. An Archaeology of the Sacred: Adena-Hopewell Astronomy and Landscape Archaeology. The Ancient Earthworks Project. 2015b. Adena-Hopewell Earthworks and the Milky Way Path of Souls. Tracing the Relational: The Archaeology of Worlds, Spirits, and Temporalities, ed. Meghan Buchanan & B. Jacob Skousen, University of Utah Press, pp. 56-84. 2018. Ancient Skywatchers of the Eastern Woodlands. Archaeology and Ancient Religion in the American Midcontinent, University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, pp. 304-342. Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. 1839. Algic Researches: Indian Tales and Legends, Vol. 1, Harper & Brothers, New York. Seeber, Pauleena, M. 1982. Eastern Algonquian Prehistory: Correlating Linguistics and Archaeology. Approaches to Algonquian Archaeology, ed. Margaret G. Hanna and Brian Kooyman, University of Calgary Archaeological Association, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Skinner Alanson. 1923. Observations on the Ethnology of the Sauk Indians, Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, Vol. 5 No. 1. Smith, Theresa S. 1995. The Island Of the Anishnaabeg: Thunderers and Water Monsters in the Traditional Ojibwe Life-World, University of Idaho Press. Smucker, Isaac. 1884. Mound Builder’s Works Near Newark, Ohio. United States Printing. Stothers, David. 1981. “Indian Hills (33WO4): A Protohistoric Assistaeronon Village in the Maumee River Valley of Northwestern Ohio.” Ontario Archaeology 36, pp. 47-56 Stothers, David and James Graves. 1983. “Cultural Continuity and Change: The Western Basin, Ontario Iroquois, and Sandusky Traditions—a 1982 Perspective.” Archaeology of Eastern North America Vol. 11, pp. 109-142. 1985. “The Prairie Peninsula Co-Tradition: An Hypothesis for Hopewellian to Upper Mississippian Continuity.” Archaeology of Eastern North America, Vol. 13, pp. 153-175. Striker, Michael. 2008. Ancestor Veneration as a Component of House Identity Formation in the Early Woodland Period. Paper presented at the 6th World Archaeological Congress, Dublin, June 2008. Tanner, John. 1956. A Narrative of the Captivity and Adventures of John Tanner During Thirty Years Residence among the Indians in the Interior of North America. Ross and Haines, Minneapolis. Tankersley, Kenneth Barnett & Robert Brand Newman. 2016. Dr. Charles Louis Metz and the American Indian Archaeology of the Little Miami River Valley, Little Miami Publishing Company, Milford, Ohio, 2016. Trowbridge, Charles Christopher. 1939. Shawnese Traditions. University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology Occasional Contributions No. 9, Ann Arbor. Vecsey, Christopher. 1983. Traditional Ojibwa Religion and its Historical Changes. American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia (PA). Voegelin, Charles Frederick. 1936. The Shawnee Female Deity. Yale University Publications in Anthropology 10, Yale University Press, New Haven. Voegelin, C.F. and E.W. Voegelin. 1944. The Shawnee Female Deity in Historical Perspective. American Anthropologist 46 (3), pp. 370-375. Webb, William S. 1940. The Wright Mounds, Sites 6 and 7, Montgomery County, Kentucky, University of Kentucky Press. 1943.The Crigler Mounds, Sites Be 20 and Be 27, and the Hartman Mound, Site Be 32, Boone County, Kentucky, Reports in Archaeology and Anthropology, 5-1.University of Kentucky, Lexington. 1959. The Dover Mound. University of Kentucky Press. Webb, Willliam S, and Charles B. Elliot. 1942. The Robbins Mounds: Sites Be 3 and Be 14, Boone County, Kentucky, With a Chapter on Physical Anthropology by Charles E. Snow, University of Kentucky, Lexington. Webb, William S. and Charles E. Snow. 1945. The Adena People, University of Kentucky, Lexington. HEALTH DISCLAIMER: This blog provides general information and discussions about health and related subjects. The information and other content provided in this blog, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment. If you or any other person has a medical concern, you should consult with your health care provider or seek other professional medical treatment. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something that have read on this blog or in any linked materials. If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor or emergency services immediately. The opinions and views expressed on this blog and website have no relation to those of any academic, hospital, health practice or other institution. Liposomal Vitamin C

Good instructions on how to make your own Liposomic Vitamin C (and more info) HERE and HERE. More general info on the benefits of Liposomal Vitamin C HERE Colloidal Silver/Ionic Silver

Mullein Leaf (Verbascum thapsus)

Black Elderberry & Elderflower (Sambucus nigra)

Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

Boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum)

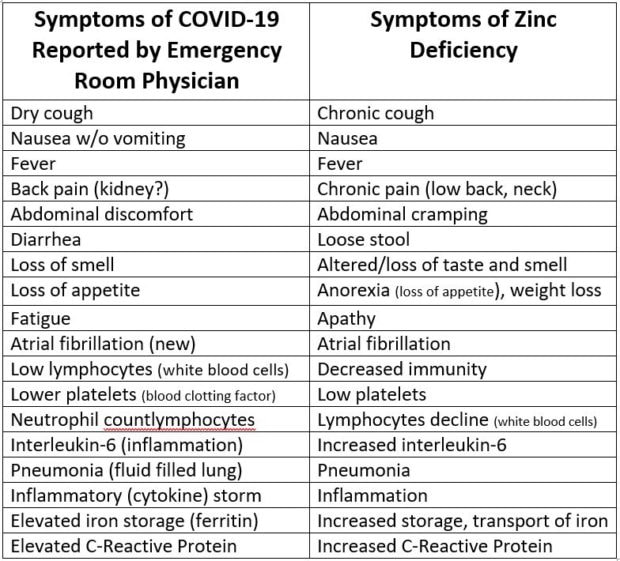

Zinc

Other Herbs Didn’t order your herbs in time? It’s not too late to make a quick dash to your local grocery store or health food store to snag some of these common-but-effective medicines. Any of the following can be made into a tea, or you can breathe them in using the steam method (lean over a bowl of boiling water with herb(s) mixed in it, with a towel over your head to keep the medicinal steam in). The ginger and garlic can even be eaten or juiced raw!

Other Common-Sense Measures