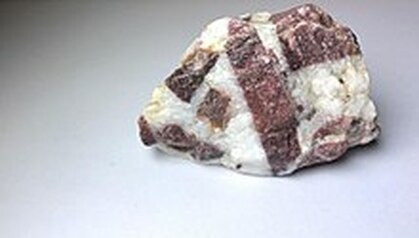

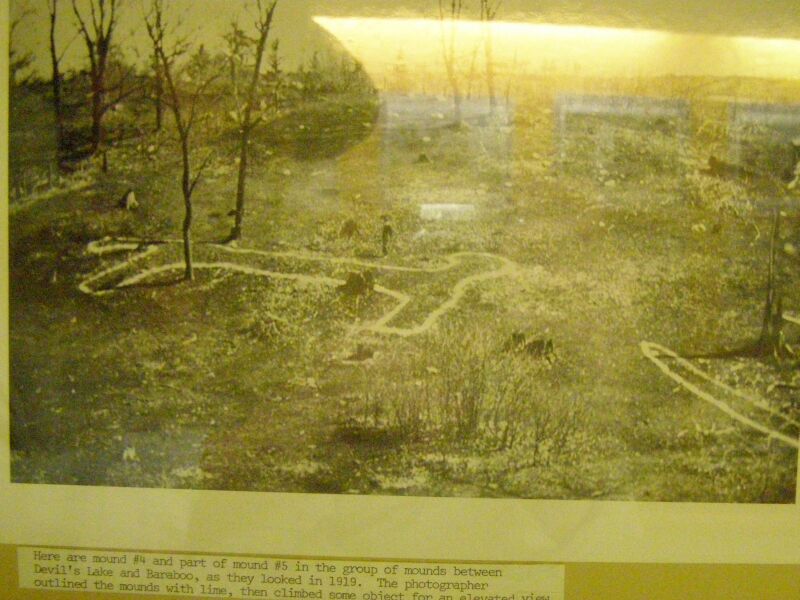

by Jason Jarrell & Sarah FarmerLocated south of Baraboo in Sauk County Wisconsin, Devil’s Lake is a place of natural wonder and legend. The central feature of the biggest State Park in Wisconsin, Devil’s Lake covers 360 acres, surrounded by quartzite bluffs reaching 500 feet in height. In 1832, a French agent of the American Fur Company named John de La Ronde visited the lake and noted that it was the echo effect of the bluffs and the “darkness of the place” which inspired the French Voyageurs to use the name Devil’s Lake(Butterfield 1880). La Ronde also mentioned an older, indigenous tradition: “The Indians gave it the name of Holy Water, declaring that there is a spirit or Manitou that resides there. I saw a quantity of tobacco…deposited there for the Manitou” (Butterfield 1880: 396). The quartzite bluffs surrounding this deceptively serene lake are of a unique composition, rendering it with intriguing purple and maroon streaks, which is caused by high concentrations of iron and hematite. This form of quartz is so unique to this region of Wisconsin that it has been named ‘Baraboo Quartz’. The “Indians” who considered the lake sacred were the Siouan speaking Ho-Chunk people, and their beliefs concerning the lake were part of an ancient and widespread cosmological model of the Eastern Woodlands, the Great Lakes, and the Plains. Ancient Model of the Cosmos The model consists of a tiered or layered cosmos comprised of three basic “worlds”. The Sky World is the region above, where birds and flying things live. It is also the habitation of the great Thunderbirds, the stars, the sun and moon, and the creator. The Earth World is the domain of mankind, plants, animals, and natural features. It could be called “our world” or the world of the living. The Earth World is a flat island or disk situated upon—and surrounded by—a primordial sea. The third world is the Underworld, a vast water filled region immediately beneath the Earth World. This Underworld is the home of fish, snakes, and aquatic animals. It is also the domain of the Great Serpent and his minions. These powerful beings often enter the Earth World through natural springs, rivers, and lakes, which are connected to the Underworld oceans by a system of caverns. Characteristics of the Great Serpent The Great Serpent manifests in a multiplicity of forms, which fall between two extremes: a gigantic horned snake and a hybrid of feline and serpent features usually known as the Underwater Panther (Lankford 2007). He is also known to be the ruler or Ogimaa(“boss”) of a race of beings of similar form (Ibid). The Great Serpent exerts a deadly influence upon the Earth World. Emerging through natural waterways, the Great Serpent destroys human beings with drowning, floods, and other calamities, including disease. The Underworld powers are also known to kidnap children and infants. The Great Serpent is also considered a source of powerful magic or medicine, which can give victory in the hunt, warfare, love, and curing or cursing individuals or entire populations (Smith 1995). One of the most commonly cited benefits of allying with the Underworld ruler is long life. Among the Anishnaabeg peoples of the northeast, medicine men that deal with the Underworld serpents are often considered practitioners of “bad medicine” (Smith 1995). Enemies of the Great Serpents The Thunderbirds of the Sky World wage an endless war upon the denizens of the Underworld. As the Great Serpents or Panthers emerge from beneath, the Thunderbirds bring down lightning and fire upon them. The Thunderers also seize their enemies and carry them into the air, tearing them to pieces. As such, the Thunderbirds are considered the allies and helpers of mankind, and are treated with great respect by Native American peoples (Smith 1995). Their war against the serpents is essential to human survival on the Earth Disk: “As the elder brothers of the Indians, the thunderers are always active in their behalf, slaying the evil snakes from the underworld whenever they dare to appear on the surface. If they did not do this these snakes would overrun the earth, devouring mankind” (Skinner 1913: 77). According to a Ho-Chunk account recorded by Folklorist Dorothy Brown (1948:14), a major battle in this ongoing war was fought at Devil’s Lake: “A quarrel once arose between the water spirits, or underwater panthers, who had a den in the depths of Devil’s Lake, and the Thunderbirds…The great birds, flying high above the lake’s surface, hurled their eggs (arrows or thunderbolts) into the waters and on the bluffs. The water monsters threw up great rocks and water-spouts from the bottom of the lake.” The Conflict at Devils Lake The Ho-Chunk tradition has it that the battle resulted in the cracked and jagged rocky surfaces of the bluffs surrounding the lake. Although the Thunderbirds were ultimately victorious, “The water spirits were not all killed and some are in Devil’s Lake to this day” (Brown 1948: 15). According to Native informants interviewed by Thomas George (1885), long ago a Ho-Chunk man fasted and prayed on the shores of the lake until one of the water spirits, “resembling a cat…with long tail and horns” rose from beneath the water and granted him the promise of long life. Brown (1948: 15) also notes that the historic Native Americans made “offerings to the spirits of this lake, by depositing tobacco on boulders on the shore or by strewing it on the water.” Historic Indians of the Great Lakes region made tobacco offerings to the Underworld spirits before water voyages in the hope of appeasing them and guaranteeing a safe voyage (Smith 1995). The Ottawa made similar offerings to “the evil spirit, whose habitation was under the water…this was sacrificed to the evil spirit, not because they loved him, but to appease his wrath” (Blackbird 1887: 79). Saunders (1946) recorded a Ho-Chuck legend in which a water spirit melted the ice and formed the channels of the Wisconsin Dells. This water spirit also formed all of the wild game and trees of the region from its own body before diving into a bottomless pit beneath Devil’s Lake. This particular water spirit was a seven headed, green serpent entity, which demanded that the Ho-Chunk sacrifice their most beautiful girls to him as offerings. One year the water spirit demanded that the daughter of the chief be sacrificed, prompting a hero named River Child to secretly conspire with an old woman to raise an army to fight the serpent. River Child had been told by Spirit Fish to strike at the left eye of the monster’s center head, apparently its one weakness. On the day of the sacrifice the secret army attacked, and River Child tricked the beast into his net. He then plunged his knife into the left eye of the center head, killing the water spirit. River Child then married the chief’s daughter and the two founded “Old River Bottom” village. The Ho-Chunk legends of the Thunderers and Underworld powers at Devil’s Lake are rooted in the prehistoric past. Around 1,000 years ago, the Effigy Mound Culture, which spanned roughly 700 to 1100 AD, constructed several mounds around Devil’s Lake. On the southeastern shore of the lake, the ancients constructed a 150 foot long bird effigy with a forked tail, described by Birmingham & Rosebrough (2017:226) as “combining characteristics of a bird and a human being.” In the traditions of the Algonquian and Siouan tribes, the Thunderbirds often assume the forms of human beings. They are often said to become winged men wielding bows, which fire lightning arrows in their conflict with the Underworld serpents. Interestingly, Birmingham & Rosebrough (2017:226-227) point out that a group of effigy mounds along the northern area of Devils Lake represent spirit entities “from the opposing lower world and include a bear, an unidentified animal, and a once-huge water spirit or panther.” The bear is another animal often connected to the Underworld in northeastern cosmology. For example, the Menomini Indians considered the actual ruler of the Underworld to be a Great White Bear (Bloomfield 1928). Obviously, the ancient mounds of Devil’s Lake align with the same cosmological belief system expressed in the Ho-Chunk traditions regarding the area, which could very well represent a continuity extending back in time to the Effigy Mound Culture. While the theory is by no means universally accepted, there have been many professional researchers who consider the Ho-Chunk to be among the actual biological descendants of the Effigy Mound builders (Green 2014). Dr. William Romain (2015) has suggested that mound builders of the Eastern Woodlands chose locations, which inspired emotion and awe in the context of the ancient cosmology to build their monuments. The dark depths and the rocky bluffs of Devil’s Lake, where even sunlight seems restricted, would certainly have created an atmosphere ripe with spirit. The mythic associations of Devil’s Lake would appear to have been widely known long before the raising of the Effigy Mounds. Boszhardt (2006) has reported a large Hopewell monitor pipe found in southeastern Minnesota, which bears etchings of horned lizard-like creatures and long tailed Underwater Panthers. The smoking pipe is made of Baraboo pipestone from one of the outcrops near Devil’s Lake (Birmingham & Rosebrough 2017: 100). The Hopewell mound building culture usually dates to between 100 BC and around 500 AD. Thus, the Devil’s Lake locality may have been considered a dwelling of the Underworld spirits for well over a millennium before the first Westerners entered the region. Jason Jarrell and Sarah Farmer are the authors of Ages of the Giants: A Cultural History of the Tall Ones in Prehistoric America: http://www.lulu.com/shop/jason-jarrell-and-sarah-farmer/ages-of-the-giants/paperback/product-23458418.html Literature Cited

(all photos from Wikimedia commons) Birmingham, Robert A. & Amy L. Rosebrough. 2017. Indian Mounds of Wisconsin, Second Edition, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison. Blackbird, Andrew J. 1887. History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan, Ypsilantian Job Printing House, Ypsilanti, Michigan. Bloomfield, Leonard. 1928. Menomini Texts, American Ethnological Society Publication 12, G.E. Stechert & Co., New York. Boszhardt, Robert F. 2006. An Etched Pipe from Southeastern Minnesota, Archaeology News 24 (2). Brown, Dorothy Moulding. 1948. Indian Place-Name Legends, Wisconsin Folklore Society, Madison. Butterfield, Wilshire (ed). 1880. The History of Columbia County, Western Historical Co., Chicago. George, Thomas J. 1885. Winnebago Vocabulary, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington. Green, William. 2014. Identity, Ideology, and the Effigy Mound-Oneota Transformation, Wisconsin Archeologist 95 (2), 44-72. Lankford, George E. 2007. The Great Serpent in Eastern North America. In Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms: Interpretations of Mississippian Iconography, ed. F. Kent Reilly and James F. Garber, University of Texas Press, Austin, 107-135. Romain, William F. 2015. An Archaeology of the Sacred: Adena-Hopewell Astronomy and Landscape Archaeology, The Ancient Earthworks Project. Saunders, Don. 1946. When the Moon is a Silver Canoe, Logston, Droste & Saunders, Wisconsin. Smith, Theresa S. 1995. The Island of the Anishnaabeg: Thunderers and Water Monsters in the Traditional Ojibwe Life-World, University of Idaho Press, Moscow.

1 Comment

There is a single cultural heritage and mythic tradition running through every history of all peoples around the world. It must be at least 25,000 years old, and it went through precisely the same stages of development throughout the entire earth.

This was reflected over time by parallel forms of shamanic beliefs and monumental construction of sacred sites. Where once there were temples of earth and stone, later there were cathedrals and sacred grounds for churches. The general cosmological model of all religions going back to the dawn of the human age is fundamentally the same. The model itself never changed, although each new form of worship did change the meanings of things within the model. Over the last several decades, an onslaught of literature, documentary films, and even one television series have focused on the “mystery” of the “ancient giants” of North America and sought to incorporate them into any one of a multitude of proposed alternate histories. Unfortunately, since one of the primary sources used to prove the existence of the Tall Ones has been the archive of thousands of newspaper reports describing the discovery of large remains throughout the United States since at least the 1800s, there are many aspects of this mystery which have become accepted as legitimate, but which in reality were the results of misreporting or outright exaggerations. While researching our book Ages of the Giants, we obtained numerous official archaeological reports, Antiquarian records, and Smithsonian documents for many of the same sites, which show up in the press archives and local histories. As such, we were able to cross reference what was actually found with what the secondary sources reported. This process lead to the debunking of many often-repeated discoveries supposedly made with the Tall Ones (i.e., bronze coins and armor), while alternately verifying or discrediting the large skeletons themselves. The reliable accounts describe the remains of individuals ranging between 7 and 8 feet in height, with large, thick crania and bones. There are a lesser number of reliable sources, which describe skeletons between 8 and 9 feet in height. It was by no means the entire population, which possessed these unique characteristics, but rather a distinct segment thereof. Ages of the Giants traces the history of these unique individuals through 4,000 years of ancient history, from 3,500 B.C. to around 500 A.D. While several major cultures associated with the Tall Ones are discussed in the book, two of the best known are the Adena and Hopewell burial mound and earthwork building traditions of the Ohio Valley, which together span roughly 1000 B.C. to around 500 A.D. In 1883 and 1884, P.W. Norris of the Smithsonian investigated 50 Adena mounds and 10 earthwork enclosures, located on both sides of the Kanawha River at Charleston, West Virginia. On November 20th, 1883, The New York Times reported the following details from Norris' excavations: "Prof. Norris, the ethnologist, who has been examining the mounds in this section of West Virginia for several months, the other day opened the big mound on Col. B. H. Smith’s farm, six or eight miles below here. This is the largest mound in the valley and proved a rich store-house...It was evidently the burial place of a noted chief, who had been interred with unusual honors. At the bottom they found the bones of a human, being measuring 7 feet in length and 19 inches across the shoulders." The mound in question is known as the Great Smith Mound, and measured around 35 feet in height, formerly located in modern Dunbar, W.V. According to the actual report filed by the Smithsonian (1), Norris found an elaborate timber vault within the Smith Mound. The structure was 13 feet long and 12 feet wide, reaching as high as 9 feet with a sloping roof (1). Six burials were discovered in the vault. The first of these was “a very large human skeleton” with two copper bracelets on the left wrist, placed in a bark coffin against the southern wall (2). The following description of the next burial discovered comes from the official Smithsonian document: "Nineteen feet from the top…in the remains of a bark coffin, a skeleton, measuring 7 ½ feet in length and 19 inches across the shoulders, was discovered. It lay on the bottom of the vault stretched horizontally on the back…Each wrist was encircled by six heavy copper bracelets…" (1) The actual field journal of P.W. Norris includes the following entry for the same burial: "At 19 feet and the bottom of this debris we find together with the fragments of a rotten bark coffin, a gigantic human skeleton 7 feet 6 inches in length..." (2) (In the list of discoveries from this mound that Norris included in his field diary, this skeleton is referred to as "human skeleton, gigantic" (2).) In this instance, not only do the primary sources confirm the discovery of the large skeleton mentioned by the Times, but the stature is measured as 5 or 6 inches greater than reported by the newspaper. In 1897, press reports surfaced describing a gigantic skeleton found by Clarence Loveberry near Chillicothe, Ohio. From the May 31st, 1897 issue of the Daily Public Ledger: “Ten skeletons were found in two mounds by Dr. Loveberry, curator of the Ohio state university museum, one that of a giant fully eight feet tall.” In May of 1897, Clarence Loveberry did indeed excavate two mounds on the Briggs farm, four miles north of Chillicothe, in Union township. The following passage is Loveberry's description of a burial from one of the mounds, republished by the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society in 1899: "Five feet deep, in the central part of the structure we found a fourth skeleton. The bones were the largest I ever removed from a mound. All joints were exceedingly massive and the muscular attachments were wonderfully developed. Badly decayed as it was, the longer bones were sound enough for me to make these observations." (3) Although Loveberry’s report does not give the specific length of the skeleton, the details certainly suggest that large remains were found. The Smithsonian sources also verify large remains reported by the press from burial mounds of the Mississippian Culture (1000--1700 A.D.). On October 10th, 1885 the Sacramento Daily Record Union ran the following story about the National Museum's work at the famous Etowah Mounds in Georgia: "A large Indian mound near the town of Cartersville, Georgia, has recently been opened and examined by a committee of scientists sent out from the Smithsonian Institution. At some depth from the surface, a kind of vault was found in which was found the skeleton of a giant measuring 7 feet 2 inches. His hair was coarse and jet black, and hung to the waist, the brow being ornamented with a copper crown. The skeleton was remarkably well preserved. Near it were also found the bodies of several children of various sizes, the remains being covered with beads made of bone of some kind. Upon removing these, the bodies were seen to be enclosed in a net of straw and reeds, and beneath this was a covering of the skin of some animal. On the stones which covered the vault were carved inscriptions, and these, when deciphered, will doubtless lift the veil that now shrouds the history of a race of giants, that at one time it is supposed, inhabited the American continent. The relics have been carefully packed and forwarded to the Smithsonian, and they are said to be the most interesting collection ever found in the United States." The large skeleton from Etowah is verified by the official Smithsonian report (1), which also offers clarification for several other details. The Etowah mounds were explored by Bureau agent John Rogan. In the lower layer of Mound C, several stone cist tombs were uncovered: "Grave a, a stone sepulcher, 2½ feet wide, 8 feet long, and 2 feet deep, was formed by placing steatite slabs on edge at the sides and ends, and others across the top. The bottom consisted simply of earth hardened by fire. It contained the remains of a single skeleton, lying on its back, with the head east. The frame was heavy and about 7 feet long. The head rested on a thin copper plate ornamented with impressed figures; but the skull was crushed and the plate injured by fallen slabs. Under the copper were the remains of a skin of some kind, and under this coarse matting, apparently of split cane…At the left of the feet were two clay vessels, one a water bottle and the other a very small vase. On the right of the feet were some mussel and sea shells and immediately under the feet two conch shells…partially filled with small shell beads. Around each ankle was a strand of similar beads. The bones and most of the shells were so far decomposed that they could not be saved." (1, Pp 302-303) In this case, the “copper crown” reported by the press was actually several copper fragments found at the head of a burial in Grave f. Indeed, the copper had preserved portions of the hair, which Rogan saved and sent to the Smithsonian (1,p. 303). The “inscribed stones” were probably a misreporting of a carved marble bust recovered by Rogan from a small mound at the site (1,p. 306). What is interesting is that in the case of the Etowah Mounds, the large remains mentioned in the media were legitimately found, while other details from the site became confused. In fact, several newspapers at the time even recorded this discovery as being from the wrong State. While verification is frequently found in the primary sources, there are other routinely reprinted press stories of large skeletons from burial mounds that are actually debunked. For example, on September 3rd, 1930 the Binghampton Press ran a story on the excavation of the Beech Bottom mound in Brooke County, W.V., reporting the central burial as "the skeleton, which was that of a man about eight feet in height", and also mentioning the discovery of "copper and bronze coins having undeciphered inscriptions." In fact, the femur measurements for this burial as given in the complete version of the official excavation report (4) indicate a stature range of 5’ 11” to 6’ 3”, if we use height estimates such as the regression formula of Trotter and Gleser (5) and absolute ratios like those of Feldesman, et al. (6) The "coins" reported from the mound are obviously explained by the numerous copper beads mentioned in the official report. The misreporting of large remains associated with bronze or copper armor seems to have been a common occurrence. Variations of the following story appeared in numerous press articles and magazines in the 1890s, describing a burial uncovered during the excavations at the famous Hopewell Mound group in Ohio: "...the excavators found near the center of the mound, at a depth of 14 feet, the massive skeleton of a man encased in copper armor. The head was covered by an oval-shaped copper cap; the jaws had copper moldings; the arms were dressed in copper, while copper plates covered the chest and stomach, and on each side of the head on protruding sticks were wooden antlers ornamented with copper." (7) The burial in this story is number 248 from Hopewell Mound 25. The following description is from the official report by Warren K. Moorehead, who explored the Hopewell Farm Mounds in 1891 and 1892 in pursuit of artifacts to display at the World's Fair: "The skeleton which was badly decayed, was 5 feet, 11 inches long. Associated with it were some very remarkable objects...A copper plate lay on the breast, and another on the abdomen, while a third lay under the hips...Cut, sawed and split bears' teeth covered the chest and abdomen, and several spool-shaped ornaments and buttons of copper were found among the ribs...The head had been decorated with a remarkable head-dress of wood and copper...The mass of copper in the centre was originally in the form of a semi-circle reaching from the lower jaw to the crown of the head...The antler-shaped ornaments were made of wood encased in sheets of copper, one-sixteenth of an inch thick."(8, p.107) Copper plates, beads, gorgets, earspools, and headdresses are all well known finds from many Hopewell sites, and the collective deposit at Hopewell Mound 25 obviously resulted in the misreport of "copper armor". These facts, along with a stature of 5 ft 11 inches for the skeleton, should obviously discount the use of this account as evidence of "copper armored giants". Alternately, there are several instances recorded in Ages of the Giants when reports of copper or bronze armor are debunked, but the large remains reported from the same sites are actually verified. In spite of the availability of this type of information, accounts of gigantic skeletons with bronze artifacts, coins, and other misreported objects are still often considered factually correct. Another popular misunderstanding is that the people who buried the large individuals in the prehistoric tombs are somehow separated from our knowledge by a veil of obscurity, leaving modern speculations and theories as the only sources of insight. Actually, the cultures that had the Tall Ones among them are the subjects of ongoing and intense archaeological research, and a primary purpose of Agesis to shed light on the ritual practices and life-ways of these ancient people. For example, current research indicates that the socio-economic system of the Adena Culture was most likely heterarchical. While individuals may temporarily assume important social roles in a heterarchical society, they do not consistently maintain power over others following the situation, which requires their expertise, such as a hunt, divination, or a ceremonial event. In fact, “chiefs” did not appear in the cultural continuum of eastern North America until around 900 A.D. with the emergence of the Mississippian Culture, and even then, the chiefly tombs do not contain large skeletal remains frequently enough to indicate a “race of giants” ruled over the population at large. The large skeletons, which are documented in the actual archaeological literature, are often found with zero to few exotic artifacts, and sometimes even in group burials with no special emphasis on the individual. In contrast, other large skeletons from Adena tombs (such as the Great Smith Mound in Charleston, mentioned above) were discovered with an abundance of goods made from special materials—such as copper, shell, or mica. This situation clearly suggests that while the Tall Ones were sometimes important people in Woodland society, they by no means inherited status in a consistent and static fashion. In some instances, Adena mounds contained large skeletons with no artifacts suggestive of important roles or status, while individuals of normal height in the same mounds were buried with numerous exotic objects. For example, at the Dover Mound in Mason County, Kentucky, a male 5 ft 5 inches tall was discovered with numerous artifacts indicative of an important shamanic role, while another skeleton 7 feet in length was simply placed with no personalized objects in a group burial. The foundations of the Late Archaic and Woodland cultures was an ancient “cult of the dead”, which reached its ultimate expression in the monumental earthworks and burial mounds of the Adena and Hopewell cultures. Current archaeological theory suggests that the burial of the dead in both natural and artificial mounds could have been intended to reference the Axis Mundi or World Tree. The Axis Mundi connected three primary realms consisting of an earth plain situated between an Above Realm and a Lower Realm or underworld (9).Through mortuary ritual, ceremonial leaders may have sought to facilitate the travel of the souls of the dead between realms. The burial of the dead from multiple communities together in the Axis Mundi likely represented the adoption of a common ancestry and mythic origins, concepts that solidified ties between multiple dispersed communities (10). The symbolism of elaborately carved stone and clay tablets found in Adena mounds in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia, as well as several Hopewell copper artifacts suggests that the shamans or ritual specialists themselves traveled the Axis Mundi in trance states, interacting with the spirits or Manitousinhabiting the cosmos. These are just a few of the subjects that we have attempted to illuminate in Ages of the Giants. The book also delves into the ancient ritual sites, settlement systems, subsistence patterns, and socio-political structures of the ancient cultures that had the Tall Ones among them. Another contribution of note is made by artist Marcia K. Moore, who created the first ever life like recreations of living Adena and Hopewell people for the book, based on photographs and measurements of actual skeletal remains (11). It is hoped that this work will serve to add clarity to a subject that has remained obscure for far too long. References

1.12th Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, ed. Cyrus Thomas, Washington, 1894. 2.P.W. Norris Mound Excavations, Smithsonian Manuscript 2400. 3.Presented by Warren K Moorehead in “Report of Field Work”, Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications, Vol. 7, Columbus, 1899. 4.Charles Bache and Linton Satterthwaite, Jr., “Exploration of an Indian Mound at Beech Bottom, West Virginia”, University of Pennsylvania, Museum Journal, Vol. 21, pp. 132-187. 5.Mildred Trotter and Goldine C. Gleser, “A Re-evaluation of Estimation of Stature Based on Measurements of Stature Taken During Life and of Long Bones After Death”, American Journal of Physical Anthropology 16, 1958, pp. 79-123. 6.M.R. Feldesman, J.G. Kleckner, and J.K. Lundy, “The femur-stature ratio and estimates of stature in mid- to late-Pleistocene fossil hominids”, American Journal of Physical Anthropology 83, 1990, pp. 359-372. 7. Reproduced here from The Dental Register Volume 46. 8. Warren K. Moorehead, The Hopewell Mound Group of Ohio, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, 1922. 9.Christopher Carr, “World View and the Dynamics of Change: The Beginning and the end of Scioto Hopewell Culture and Lifeways”, The Scioto Hopewell and Their Neighbors: Bioarchaeological Documentation and Cultural Understanding,ed. D. Troy Case and Christopher Carr, Springer Science and Business Media, 2008, pp. 289-333. 10.Christopher Carr, “The Tripartite Ceremonial Alliance among Scioto Hopewellian Communities and the Question of Social Ranking”, in Gathering Hopewell: Society, Ritual, and Ritual Interaction, ed. Christopher Carr and D. Troy Case, Springer, 2006, pp. 258-338. 11. See Adena and Hopewell recreations on www.paradigmcollision.com, and www.marciakmoore.com. Ancient Americans developed advanced copper working before the rest of the world.

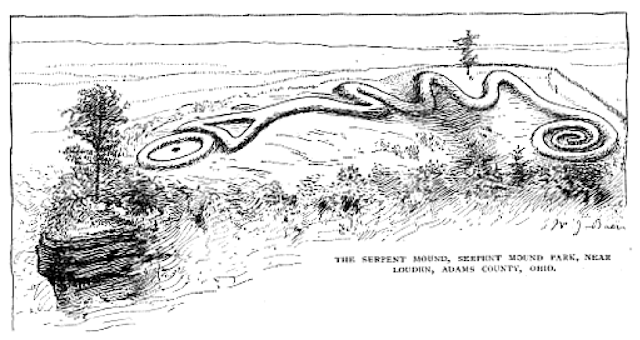

As documented in Ages of the Giants, prehistoric people in America were fabricating sophisticated spear points and other useful objects from copper by 6,000 B.C. Three thousand years later Western European finally got around to making simple copper beads. With this early start at metallurgy, it is no surprise that by Hopewell times (200 B.C.), the Indians were creating truly fantastic copper effigies, head plates, and geometric designs. Recently, a debate has developed in the Ohio archaeological community over the age and cultural affiliations of the Great Serpent Mound in Adams County, Ohio. Serpent Mound is the greatest effigy mound in the Ohio Valley. The earthen mound is 1,348 feet long and portrays a serpent with a coiled tail with what has been interpreted as an egg at its mouth. In the 1800s, Frederick Ward Putnam excavated several mounds and other burials in the vicinity of the Great Serpent (1). At least two of the mounds yielded evidence, which today would be recognized as diagnostic of the Adena Culture (1000 B.C.—300 A.D.), while several non-mounded burials resemble Late Archaic (2500—500 B.C.) tombs as found elsewhere in Ohio. There is much more cultural information from Putnam’s excavations that archaeological institutions have never made available to the public in a comprehensive format, but this situation is soon to be remedied (2). In addition to the evidence recovered in the 1800s, a recent project at Serpent Mound radiocarbon dated the earliest phase of the effigy to around 321 B.C. (3), placing the origin of the mound in the Early Woodland period, which is defined by the Adena Culture. In spite of the Adena evidence, influential organizations have continued to back an alternative interpretation of the Great Serpent Mound which associates the effigy with the much more recent Fort Ancient Culture manifestation (1000—1600 A.D). Adena

One of the criteria recently given for rejecting an Adena affiliation for the Great Serpent Mound is “the virtual absence of serpent imagery in the Adena culture” (4). However, evidence from several archaeological sites reveals that indeed, the Adena Culture didutilize serpent symbolism in a presumably ritual context, and may have even passed the mythology behind the serpent to their contemporaries and successors in the Hopewell Culture. The Adena-affiliated Wright Mound was located in Montgomery County, Kentucky, and was excavated in the late 1930s (5). The mound contained over 20 burials, some in typical Late Adena log tombs. Calibrated radiocarbon dates from the mound include 120 A.D. and 264 A.D. (6). Burial 11 at Wright consisted of an extended skeleton in a tomb with two logs at each end and side. The body had been laid upon strips of bark, and bark also covered the tomb. The skeleton featured a copper bracelet on each arm and a shell disk bead necklace under the chin. Another “artifact” with Burial 11 recorded by William S. Webb was a serpent skeleton: “Between the femora was the skeleton of a large snake. This appears to have been an intentional placement and not the result of the death of a transient snake visitor seeking winter quarters.” (5, pp. 35-37) A similar discovery was documented for Wright Burial 18, which was another extended skeleton in a rectangular log tomb. This burial featured two copper bracelets on each forearm. According to Webb, “At the foot of the burial there was the complete skeleton of a large snake, fairly well preserved.” (5, p. 46) There is another possible example of Adena serpent symbolism from elsewhere in Kentucky. In 1988, Sara L. Sanders surveyed a stone serpent mound situated on a ridge top overlooking the Big Sandy River in Boyd County, Kentucky on the property of Ashland Oil (7). The present authors recently summarized several details of this site in Ages of the Giants: A Cultural History of the Tall Ones in Prehistoric America(Serpent Mound Books & Press, 2017): “At the time of Sara L Sanders’ survey in 1988, the serpent was 191.4 m in length, the head being 25.6 m long and 11 m wide. The tail was 7.2 m at the widest point and 2.05 m at the narrowest. The serpent was composed entirely of sandstone, the head facing east towards the River. The piled sandstone integrates natural “float rock” into the design. On a lower ledge below the serpent, a semi-circular stone structure 5.2 m in diameter built atop a sandstone outcrop has been interpreted to represent an egg. Sanders considered the Kentucky Serpent to be immediately comparable to the more famous earthen serpent in Ohio.” While the Kentucky serpent has not been radiocarbon dated, information has been obtained from another stone structure in Boyd County, which may have been constructed by the same community that built the stone effigy. The Viney Branch Stone Mound was also situated to overlook the Big Sandy Valley and has produced calibrated radiocarbon ranges of 890-215 B.C. and 798-1 B.C. (8). This chronology overlaps the periods of the Late Archaic and Adena cultures in the Ohio Valley. The Viney Branch mound contained two cremations, and also covered a crematory and hearth. One of the cremations was placed in a pit. These features are similar to Late Archaic and very early Adena mounds (9). Another little known stone Serpent Mound was located in West Virginia, situated on a ridgeline overlooking the town of Omar in Logan County. The West Virginia serpent was surveyed by Gary Wilkins in 1979, and found to be “similar in form to serpent mounds found in Kentucky and Ohio” (10, p. 1). The authors also summarized this effigy in Ages of the Giants: “The serpent was oriented north, the head consisting of an oval ring of stone with a rectangular flat rock at the center. The serpent was composed of large, flat sandstone rocks, extending in undulating fashion over 80 feet to the south, where it joined a natural rock outcrop incorporated into the design. The artificial wall varied between 1 and 3 feet in height and 1.6 and 8 feet in width at the time of the survey. The “natural” section was also aligned with the ridge and extended around 51 feet further to the south.” Wilkins Himself suggested that the West Virginia stone serpent was “probably late Adena to early Hopewell in age” (10, p. 3). Serpent symbolism has also been documented from Adena sites outside of the Ohio River Valley. Several major Adena sites have been excavated on the East Coast, usually grouped under the cultural label of Delmarva Adena. It is a popular trend in modern studies to explain Adena elements on the East Coast as the simple product of exchange. However, it has been pointed out that regional manifestations of Adena appear in the archaeological record around 800 B.C., emerging from a local formulation of the Late Archaic cultural network (11). This is almost identical to the late Adena expert Don Dragoo’s theory for the origin of Adena in the Ohio Valley (9). Besides the chronology, Delmarva Adena ritualism is also closely linked to the Ohio Valley culture. T. Latimer Ford once pointed out that the number of diagnostic artifacts found at the Demarva Adena site at Sandy Hill in Maryland “far exceeds that recovered from any Ohio or Kentucky Adena site.” (12, p. 86) Commenting on the obvious Adena ritualism at the West River site on Chesapeake Bay, Ford stated in 1976, “While the artifacts might have been trade goods, the cremation and burial traits are not likely to have been diffused to local tribes.” (12, p. 75) There are other Delmarva Adena ceremonial practices, which have been demonstrably connected with the Ohio Valley. For example, the upper medial and lateral incisors and supporting bone of a skull buried at the Rosenkrans site in New Jersey had been intentionally broken out. Herbert C. Kraft suggested that this had been done to allow for the insertion of a worked wolf jaw spatula as reported from the Wright and Ayers Mounds in Kentucky and the Wolford Mound in Ohio, allowing the individual to become a “wolf shaman”(13, p. 29). With these important ties to Ohio Valley Adena established, it is interesting to note that obvious serpent symbolism has been found at the Delmarva Adena affiliated Boucher site located east of Lake Champaign in Vermont. Three hide medicine bags from the Boucher site are considered part of the paraphernalia of local shamanic practitioners or ritual specialists. One of the hide bags contained the bones of a black snake covered in red ocher, while another bag contained copper fragments (14). The third bag, found near the chest area of a middle-aged male, contained bones of a timber rattler, a black rat snake, American mink, pine marten, cervid, duck, and red fox, as well as a raccoon bacculum, a bone fish hook, and two pebbles (Ibid). The radiocarbon range of the Boucher Site is 885—114 B.C., and at least 15 Adena-style tubular pipes from the site were made of Ohio fireclay (Ibid). Ohio and Illinois Hopewell Returning to the Ohio Valley, serpent symbolism was also present in the contemporaries and successors of Adena in the Hopewell Culture (200 B.C.—500 A.D). Christopher Carr and Robert McCordhave recently published a fascinating study of four “composite creature” effigies from the Hopewellian Turner Earthworks in the Little Miami valley (15; 16). The four effigies feature elements of rattlesnakes, fish, salamanders, crocodilians, and bear or badger. Carr and McCord suggest that the Turner effigies could represent a very ancient form of the mythic entity, which later evolved to become the “Great Horned Serpent/Underwater Panther” of the historic Native American tribes—albeit from a time before the archetype was associated with Above-World animal elements (such as wings). Basic serpent symbolism has been found at other Ohio Hopewell sites. As an example, a group of four sandstone tablets from Mound 1 of the Hopewell Mound Group in Ross County are engraved with effigies of a diamondback rattlesnake, the body formed in a “Z” shape (15). Beyond Ohio, serpent symbolism very similar to that documented from Ohio Valley Adena sites has been found in Hopewell burial mounds in Illinois. The Utica Mound Group consists of 3 groups of 27 mounds located on the Illinois River south of Utica, Illinois. Beneath Mound 1 of Group 1, an effigy comprised of hundreds of stones was uncovered about 20 inches above the mound base, described as “A large quantity of rock, which appears to be a large effigy of a snake…” (17, p. 63). The stone serpent measured 25 x 17 feet, and enclosed a central burial area originally containing at least 14 burials. In Mound 3 of group 1 at Utica, the bones of a snake were found placed over the frontal bones of two disarticulated skeletons. In Mound 11 of the same group, two skeletons extended side by side (Burials 10 and 11) also featured a snake skeleton placed over the frontal bones. Finally, a snake skeleton had been placed near the right shoulder of the skeleton of a young female in Mound 1 of Group 2. The stone serpent effigy and the snake skeletons placed with burials at Utica Mounds are strongly reminiscent of the Adena practices discussed in this article. Similar discoveries were also made at the Adler group of 8 Hopewell mounds near Joliet and the Des Plaines River in Will County, Illinois (18). Beneath Adler Mound 3, a central sub-floor tomb containing the remains of five individuals placed shoulder to shoulder, as well as the skeletons of two infants was uncovered. According to Howard Winters, “With the exception of the two infants in the lower portion of the tomb, all burials were found with the articulated vertebrae of snakes placed several centimeters above their waists.” (18, p. 62) In Adler Mound 7, a tomb was found containing the remains of 4 individuals. Above the waist of one of the burials were found “snake vertebrae, again intentionally placed in that position.” (18, p. 73) Finally, Adler Mound 8 covered a sub floor tomb containing 3 extended burials and one large bundle reburial. Only the skeleton of a young adult male was associated with grave goods. Regarding this burial, Winters notes, “the vertebrae of a bull snake (?) were draped across and above the waist, as in Mounds 3 and 7.” (18, p. 73) The Great Serpent of Southern Ontario The local manifestation of the Hopewell Culture in southern Ontario, Quebec, and New York State is usually referred to as Point Peninsula. People participating in the Hopewell/Point Peninsula Culture constructed a Serpent Mound of their own at Roach’s Point on Rice Lake in Peterborough County, Ontario. The Middle Woodland component of the site consist of nine burial mounds, one of which—Mound E—is considered by many to be a serpent effigy (19; 20). The Mound E serpent is 194 feet in length and 25 feet wide at the base, with a maximum height of 5-6 feet. Mound F is located very near the head of the serpent, and has been interpreted as an “egg” similar to that before the head of the Great Serpent Mound in Ohio. The Mound F egg contained at least six burials, one of which was a “trophy skull” burial as found at many Adena and Hopewell sites in Ohio (21). David Boyle found that Mound F also contained a layer of earth mixed with ash and mussel shells 4 feet from the surface at mound center, and beneath this at the mound floor was a stone circle 3 feet in diameter, which exhibited evidence of fire (Ibid). These features are very similar to those documented by Squier and Davis within the ovular “egg” at the mouth of the Great Serpent Mound in Ohio: “The ground within the oval is slightly elevated: a small circular elevation of large stones much burned once existed in its centre; but they have been thrown down and scattered by some ignorant visitor, under the prevailing impression probably that gold was hidden beneath them.” (22, p. 97) The Rice Lake serpent was also a burial mound, and may have once contained the remains of at least 60 individuals (19). The burials were likely accretional and span several eras, but the oldest were those placed in burial pits beneath the mound and on the mound floor, with such artifacts as copper, shell, and silver beads, mandibles of timber wolf, bird, and bear, beak of loon, a limestone animal effigy, and a massive double-bitted adze (19; 20). While these burials may seem to strongly differentiate the Rice Lake serpent from its Ohio counterpart, this is not the case. For while Ohio Valley archaeologists largely continue to insist that the Great Serpent Mound in Adams County was not a burial mound, recent research by Jeffrey Wilson (23) has proven that although they were forgotten and poorly documented, burials wererecovered from the Ohio Serpent sometime in the late 1800s. With regards to the cultural influences and affiliations of the Rice Lake Serpent, Michael Spence and J. Russell Harper state, “Mound burial might be a Hopewellian trait, though the serpent shape is possibly related to the Serpent Mound of Ohio, seemingly Adena.” (24, p. 55) Indeed, radiocarbon dates for the Mound E serpent span 128—302 A.D., overlapping the temporal range of Late Adena and Hopewell in the Ohio Valley and elsewhere (25). The Rice Lake Serpent is located in the vicinity of numerous burial mounds, which have yielded extensive evidence of Hopewell influence. Regional Connections and Conclusion The purpose of this article is to demonstrate the serpent symbolism of several Adena and Hopewell sites. The authors suggest that in light of this evidence, there is no reason why the Great Serpent Mound in Adams County Ohio—located near the epicenter of Adena and Hopewell—could not be considered as possibly being a site of one or the other, if not both of these cultures. This is especially true in light of much of the evidence (including early radiocarbon dates) collected by William Romain and his associates in recent years. One objection to this article will undoubtedly be that the sites mentioned are from Kentucky, Illinois, West Virginia, the East Coast, and Southern Ontario, while the Great Serpent Mound is located in Southern Ohio. However, we would point out that the archaeological record strongly suggests close cultural connections between the Ohio Valley Adena and Hopewell and the manifestations beyond. Furthermore (and perhaps most importantly), the recent evidence obtained from DNA research (26) and studies of physical skeletal morphology (27) clearly reveal that actual peoplespread out from the Ohio Valley during the time of Adena and Hopewell, likely taking new ideas and forms of ritualism with them. One of these ideas may well have been a ceremonialism and veneration of an early form of the Great Serpent, as represented at Ohio’s Great Serpent Mound. References 1. F.W. Putnam, “The Serpent Mound of Ohio”, The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Vol. 39. 2. Jeffrey Wilson, forthcoming. 3. William F. Romain, “New Radiocarbon Dates Suggest Serpent Mound is More Than 2,000 Years Old”, The Ancient Earthworks Project, 2014, http://ancientearthworksproject.org/1/post/2014/07/new-radiocarbon-dates-suggest-serpent-mound-is-more-than-2000-years-old.html 4. Bradley T. Lepper, “On the Age of Serpent Mound: A Reply to Romain and Colleagues”, Midcontinental Journal of ArchaeologyVol. 43 (1), 2018, pp. 62-75. 5. William S. Webb, The Wright Mounds, sites 6 and 7, Montgomery County, Kentucky, University of Kentucky Press, 1940. 6. Robert F. Maslowski, Charles M. Niquette, and Derek M. Wingfield, “The Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia Radiocarbon Database”, West Virginia Archeologist, Vol. 47:1-2. 7. Sara L Sanders, “The Stone Serpent Mound of Boyd County, Kentucky: An Investigation of a Stone Effigy”, Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology,16 (2). 8. Darlene Applegate, “Chapter 5: Woodland Period”, in The Archaeology of Kentucky: An Update, ed. David Pollack, State Historic Preservation Comprehensive Plan Report No. 3, Kentucky Heritage Council, Frankfort, 2008, pp. 339-604. 9. Don W. Dragoo, Mounds for the Dead: An Analysis of the Adena Culture, Annals of the Carnegie Museum, Vol. 37, 1963. 10.Gary R. Wilkins, “A Rock Serpent Mound in Logan County, West Virginia”, Tennessee Anthropological Association Newsletter, Vol. 6 (4), 1981, pp. 1-4. 11.Jay F. Custer, “New Perspectives on the Delmarva Adena Complex”, Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology, 12 (1), 1987, pp. 35-53. 12.T. Latimer Ford, Jr., “Adena Sites on Chesapeake Bay”, Archaeology of Eastern North America, Vol. 4, 1976, pp. 63-89. 13.Herbert C. Kraft, “The Rosenkrans Site, An Adena-Related Mortuary Complex in the Upper Delaware Valley, New Jersey”, Archaeology of Eastern North America, Vol. 4, 1976, pp. 9-50. 14.Michael J. Heckenberger, James B. Petersen, Ellen R. Cowie, Arthur E. Spiess, Louise A. Basa and Robert E. Stuckenrath, “Early Woodland Period Mortuary Ceremonialism in the Far Northeast: a View from the Boucher Cemetery”, Archaeology of Eastern North America18, 1990, pp. 109-144. 15.Christopher Carr and Robert McCord, “Ohio Hopewell Depictions of Composite Creatures Part 1—Biological Identification and Ethnohistorical Insights”, Midcontinental Journal of ArchaeologyVol. 38 No.1, 2013, pp. 5-82. 16.Christopher Carr and Robert McCord, “Ohio Hopewell Depictions of Composite Creatures Part 2—Archaeological Context and a Journey to an Afterlife”, Midcontinental Journal of ArchaeologyVol. 40 No.1, 2015, pp. 18-47. 17.Henry C. Henriksen, “Utica Hopewell, A Study of Early Hopewellian Occupation in the Illinois River Valley”, Illinois Archaeological Survey Bulletin No. 5, University of Illinois, Urbana, 1965, pp. 1-67. 18.Howard Winters, “The Adler Mound Group, Will County, Illinois”, Illinois Archaeological Survey Bulletin No. 3, University of Illinois, Urbana, 1961, pp. 57-88. 19.Jeffrey Bryan Dillane, Visibility Analysis of the Rice Lake Burial Mounds and Related Sites, Master of Arts Thesis, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, 2010. 20.Jason Jarrell and Sarah Farmer, “The Burial Mounds and Woodland Traditions of Canada”, Ancient AmericanIssue 114, 2016. 21.David Boyle, “Mounds”, Annual Archaeological Report, Ontario, 1897, pp. 14-57. 22.Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, Bartlett & Welford, New York, 1848. 23.Jeffrey Wilson, “The Mysterious Excavations of Serpent Mound”, presentation at Friends of Serpent Mound Mysteries Day event, August 21st, 2016, and forthcoming book. 24.Michael Spence and J. Russell Harper, “The Cameron’s Point Site”, Royal Ontario Museum, Art and Archaeology Occasional Paper 12, Toronto, 1968. 25.Richard B. Johnston, The Archaeology of the Serpent Mounds Site, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, 1968, pp. 70-72. 26.Deborah A. Bolnick and David Glenn Smith, “Migration and Social Structure Among The Hopewell: Evidence from ancient DNA”, in American Antiquity, 72 (4), pp. 627-644. 27.P.J. Pennefather-O’Brien, Biological Affinities Among Middle Woodland populations associated with the Hopewell Horizon, PhD Dissertation, Indiana University, 2006. |

About UsWe are explorers of cosmology, anthropology, philosophy, medicine, and religion. Archives

October 2020

Categories

All

|

Photo used under Creative Commons from John Brighenti

RSS Feed

RSS Feed