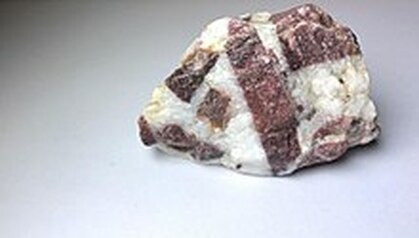

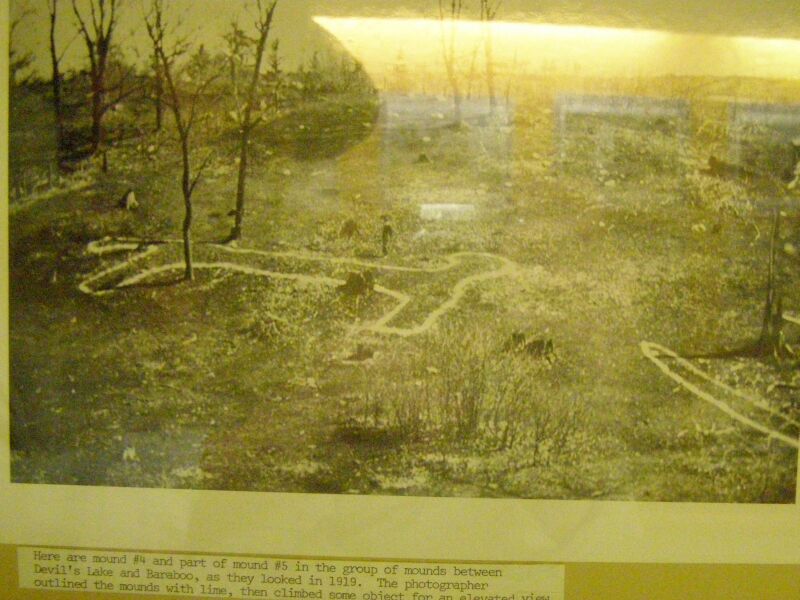

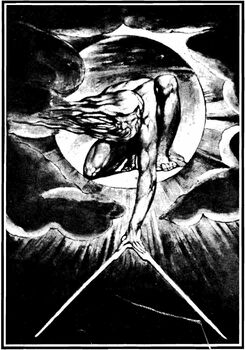

by Jason Jarrell & Sarah FarmerLocated south of Baraboo in Sauk County Wisconsin, Devil’s Lake is a place of natural wonder and legend. The central feature of the biggest State Park in Wisconsin, Devil’s Lake covers 360 acres, surrounded by quartzite bluffs reaching 500 feet in height. In 1832, a French agent of the American Fur Company named John de La Ronde visited the lake and noted that it was the echo effect of the bluffs and the “darkness of the place” which inspired the French Voyageurs to use the name Devil’s Lake(Butterfield 1880). La Ronde also mentioned an older, indigenous tradition: “The Indians gave it the name of Holy Water, declaring that there is a spirit or Manitou that resides there. I saw a quantity of tobacco…deposited there for the Manitou” (Butterfield 1880: 396). The quartzite bluffs surrounding this deceptively serene lake are of a unique composition, rendering it with intriguing purple and maroon streaks, which is caused by high concentrations of iron and hematite. This form of quartz is so unique to this region of Wisconsin that it has been named ‘Baraboo Quartz’. The “Indians” who considered the lake sacred were the Siouan speaking Ho-Chunk people, and their beliefs concerning the lake were part of an ancient and widespread cosmological model of the Eastern Woodlands, the Great Lakes, and the Plains. Ancient Model of the Cosmos The model consists of a tiered or layered cosmos comprised of three basic “worlds”. The Sky World is the region above, where birds and flying things live. It is also the habitation of the great Thunderbirds, the stars, the sun and moon, and the creator. The Earth World is the domain of mankind, plants, animals, and natural features. It could be called “our world” or the world of the living. The Earth World is a flat island or disk situated upon—and surrounded by—a primordial sea. The third world is the Underworld, a vast water filled region immediately beneath the Earth World. This Underworld is the home of fish, snakes, and aquatic animals. It is also the domain of the Great Serpent and his minions. These powerful beings often enter the Earth World through natural springs, rivers, and lakes, which are connected to the Underworld oceans by a system of caverns. Characteristics of the Great Serpent The Great Serpent manifests in a multiplicity of forms, which fall between two extremes: a gigantic horned snake and a hybrid of feline and serpent features usually known as the Underwater Panther (Lankford 2007). He is also known to be the ruler or Ogimaa(“boss”) of a race of beings of similar form (Ibid). The Great Serpent exerts a deadly influence upon the Earth World. Emerging through natural waterways, the Great Serpent destroys human beings with drowning, floods, and other calamities, including disease. The Underworld powers are also known to kidnap children and infants. The Great Serpent is also considered a source of powerful magic or medicine, which can give victory in the hunt, warfare, love, and curing or cursing individuals or entire populations (Smith 1995). One of the most commonly cited benefits of allying with the Underworld ruler is long life. Among the Anishnaabeg peoples of the northeast, medicine men that deal with the Underworld serpents are often considered practitioners of “bad medicine” (Smith 1995). Enemies of the Great Serpents The Thunderbirds of the Sky World wage an endless war upon the denizens of the Underworld. As the Great Serpents or Panthers emerge from beneath, the Thunderbirds bring down lightning and fire upon them. The Thunderers also seize their enemies and carry them into the air, tearing them to pieces. As such, the Thunderbirds are considered the allies and helpers of mankind, and are treated with great respect by Native American peoples (Smith 1995). Their war against the serpents is essential to human survival on the Earth Disk: “As the elder brothers of the Indians, the thunderers are always active in their behalf, slaying the evil snakes from the underworld whenever they dare to appear on the surface. If they did not do this these snakes would overrun the earth, devouring mankind” (Skinner 1913: 77). According to a Ho-Chunk account recorded by Folklorist Dorothy Brown (1948:14), a major battle in this ongoing war was fought at Devil’s Lake: “A quarrel once arose between the water spirits, or underwater panthers, who had a den in the depths of Devil’s Lake, and the Thunderbirds…The great birds, flying high above the lake’s surface, hurled their eggs (arrows or thunderbolts) into the waters and on the bluffs. The water monsters threw up great rocks and water-spouts from the bottom of the lake.” The Conflict at Devils Lake The Ho-Chunk tradition has it that the battle resulted in the cracked and jagged rocky surfaces of the bluffs surrounding the lake. Although the Thunderbirds were ultimately victorious, “The water spirits were not all killed and some are in Devil’s Lake to this day” (Brown 1948: 15). According to Native informants interviewed by Thomas George (1885), long ago a Ho-Chunk man fasted and prayed on the shores of the lake until one of the water spirits, “resembling a cat…with long tail and horns” rose from beneath the water and granted him the promise of long life. Brown (1948: 15) also notes that the historic Native Americans made “offerings to the spirits of this lake, by depositing tobacco on boulders on the shore or by strewing it on the water.” Historic Indians of the Great Lakes region made tobacco offerings to the Underworld spirits before water voyages in the hope of appeasing them and guaranteeing a safe voyage (Smith 1995). The Ottawa made similar offerings to “the evil spirit, whose habitation was under the water…this was sacrificed to the evil spirit, not because they loved him, but to appease his wrath” (Blackbird 1887: 79). Saunders (1946) recorded a Ho-Chuck legend in which a water spirit melted the ice and formed the channels of the Wisconsin Dells. This water spirit also formed all of the wild game and trees of the region from its own body before diving into a bottomless pit beneath Devil’s Lake. This particular water spirit was a seven headed, green serpent entity, which demanded that the Ho-Chunk sacrifice their most beautiful girls to him as offerings. One year the water spirit demanded that the daughter of the chief be sacrificed, prompting a hero named River Child to secretly conspire with an old woman to raise an army to fight the serpent. River Child had been told by Spirit Fish to strike at the left eye of the monster’s center head, apparently its one weakness. On the day of the sacrifice the secret army attacked, and River Child tricked the beast into his net. He then plunged his knife into the left eye of the center head, killing the water spirit. River Child then married the chief’s daughter and the two founded “Old River Bottom” village. The Ho-Chunk legends of the Thunderers and Underworld powers at Devil’s Lake are rooted in the prehistoric past. Around 1,000 years ago, the Effigy Mound Culture, which spanned roughly 700 to 1100 AD, constructed several mounds around Devil’s Lake. On the southeastern shore of the lake, the ancients constructed a 150 foot long bird effigy with a forked tail, described by Birmingham & Rosebrough (2017:226) as “combining characteristics of a bird and a human being.” In the traditions of the Algonquian and Siouan tribes, the Thunderbirds often assume the forms of human beings. They are often said to become winged men wielding bows, which fire lightning arrows in their conflict with the Underworld serpents. Interestingly, Birmingham & Rosebrough (2017:226-227) point out that a group of effigy mounds along the northern area of Devils Lake represent spirit entities “from the opposing lower world and include a bear, an unidentified animal, and a once-huge water spirit or panther.” The bear is another animal often connected to the Underworld in northeastern cosmology. For example, the Menomini Indians considered the actual ruler of the Underworld to be a Great White Bear (Bloomfield 1928). Obviously, the ancient mounds of Devil’s Lake align with the same cosmological belief system expressed in the Ho-Chunk traditions regarding the area, which could very well represent a continuity extending back in time to the Effigy Mound Culture. While the theory is by no means universally accepted, there have been many professional researchers who consider the Ho-Chunk to be among the actual biological descendants of the Effigy Mound builders (Green 2014). Dr. William Romain (2015) has suggested that mound builders of the Eastern Woodlands chose locations, which inspired emotion and awe in the context of the ancient cosmology to build their monuments. The dark depths and the rocky bluffs of Devil’s Lake, where even sunlight seems restricted, would certainly have created an atmosphere ripe with spirit. The mythic associations of Devil’s Lake would appear to have been widely known long before the raising of the Effigy Mounds. Boszhardt (2006) has reported a large Hopewell monitor pipe found in southeastern Minnesota, which bears etchings of horned lizard-like creatures and long tailed Underwater Panthers. The smoking pipe is made of Baraboo pipestone from one of the outcrops near Devil’s Lake (Birmingham & Rosebrough 2017: 100). The Hopewell mound building culture usually dates to between 100 BC and around 500 AD. Thus, the Devil’s Lake locality may have been considered a dwelling of the Underworld spirits for well over a millennium before the first Westerners entered the region. Jason Jarrell and Sarah Farmer are the authors of Ages of the Giants: A Cultural History of the Tall Ones in Prehistoric America: http://www.lulu.com/shop/jason-jarrell-and-sarah-farmer/ages-of-the-giants/paperback/product-23458418.html Literature Cited

(all photos from Wikimedia commons) Birmingham, Robert A. & Amy L. Rosebrough. 2017. Indian Mounds of Wisconsin, Second Edition, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison. Blackbird, Andrew J. 1887. History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan, Ypsilantian Job Printing House, Ypsilanti, Michigan. Bloomfield, Leonard. 1928. Menomini Texts, American Ethnological Society Publication 12, G.E. Stechert & Co., New York. Boszhardt, Robert F. 2006. An Etched Pipe from Southeastern Minnesota, Archaeology News 24 (2). Brown, Dorothy Moulding. 1948. Indian Place-Name Legends, Wisconsin Folklore Society, Madison. Butterfield, Wilshire (ed). 1880. The History of Columbia County, Western Historical Co., Chicago. George, Thomas J. 1885. Winnebago Vocabulary, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington. Green, William. 2014. Identity, Ideology, and the Effigy Mound-Oneota Transformation, Wisconsin Archeologist 95 (2), 44-72. Lankford, George E. 2007. The Great Serpent in Eastern North America. In Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms: Interpretations of Mississippian Iconography, ed. F. Kent Reilly and James F. Garber, University of Texas Press, Austin, 107-135. Romain, William F. 2015. An Archaeology of the Sacred: Adena-Hopewell Astronomy and Landscape Archaeology, The Ancient Earthworks Project. Saunders, Don. 1946. When the Moon is a Silver Canoe, Logston, Droste & Saunders, Wisconsin. Smith, Theresa S. 1995. The Island of the Anishnaabeg: Thunderers and Water Monsters in the Traditional Ojibwe Life-World, University of Idaho Press, Moscow.

1 Comment

There is a single cultural heritage and mythic tradition running through every history of all peoples around the world. It must be at least 25,000 years old, and it went through precisely the same stages of development throughout the entire earth.

This was reflected over time by parallel forms of shamanic beliefs and monumental construction of sacred sites. Where once there were temples of earth and stone, later there were cathedrals and sacred grounds for churches. The general cosmological model of all religions going back to the dawn of the human age is fundamentally the same. The model itself never changed, although each new form of worship did change the meanings of things within the model. |

About UsWe are explorers of cosmology, anthropology, philosophy, medicine, and religion. Archives

October 2020

Categories

All

|

Photo used under Creative Commons from John Brighenti

RSS Feed

RSS Feed